Saturday's Duck Soup Cinema was OK by me. But at least this time I was prepared.

The Madison revue, which presents an hour of vaudeville followed by a silent film with live organ accompaniment in the Overture Center, has a pretty large following, mostly among families and the elderly. (One of the most remarkable things about Sunday's Madison Opera performance of The Magic Flute is that they somehow managed to find patrons even older than those who attend Duck Soup; folks in their nineties were hobbling out to find their seats.) I've never minded that I, as a 29-year-old, look a little out of place at Duck Soup. It's a chance to see silent cinema with live music, so I show up and I'm happy to be there. Besides, we had a higher quotient of older customers at the Organ Loft in Salt Lake City (where silent films were also shown), and for Utahns it's a bit more frightening, understanding that the older you are in SLC, the greater a chance that you're a practicing polygamist. But anyhow. The first time we went to Duck Soup Cinema was in one of its last appearances at the Oscar Meyer Theatre at the old Overture Center; Duck Soup has been running off and on since the early 80's, only growing more popular over the years until it began to play sold out shows, so there was a bittersweet feeling as they went through the vaudeville before an amazingly raucous crowd (those old folks can still kick it up) enjoyed Harold Lloyd's classic Speedy.

We tried to make the Buster Keaton film Seven Chances last year, but it was already sold out when we arrived two hours early. We were smarter this year and bought our tickets to the two spring Duck Soup programs, Harold Lloyd's Safety Last! and a collection of shorts by Charlie Chaplin, as soon as they became available. We took my wife's parents to Safety Last! so they could have their first encounter with the magic we felt when we attended Speedy.

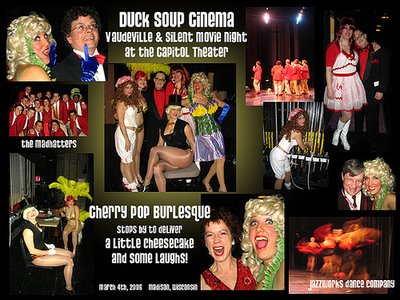

Instead, the vaudeville was mildly shocking. Not to me so much, but my empathetic nerve was twitching. The crowd--again, mostly senior citizens and families with very young children--were treated to an appearance by the Cherry Pop Burlesque, a Madison-based group that presents scantily clad (or not clad at all) women with men in animal costumes and lots of smarmy jokes. Apart from one gal wearing not much at all, most were relatively clothed, and Olive Talique (Angela Richardson) was very, very funny doing a thick Bronx accent and spreading her arms as she talked, as though trying to physically describe how broad was her comedy. The laughs from the audience were sporadic. Many of us were laughing. Others--the mothers in the crowd, I think--just kind of let their jaws drop while they covered the eyes of their children. The Cherry Pop folks, who were plugging an upcoming adults-only show at the Overture Center, left to polite applause and were replaced by Jazzworks, a group of fit girls in leotards who dance expressively and suggestively to songs from "Chicago" and the like. You know, the kind of songs about how you know how to dress to please your man, and how pleased he's going to see you when he sees you in that new number you bought, and dump that other girl, and so on, while groins gyrate. The young boy sitting ahead of me, who had expressed some interest in the women of the Cherry Pop burlesque, leaned forward each time the dancers left the stage between songs, and each time leaned further forward, until one could wager as to whether he'd hit the floor or puberty first.

At last the Jazzworks girls left, and something new was in the air: tension, you'd call it. Some of us were pleased, some of us not so much. At last the most harmless moment in the evening arrived, when the truly terrible a-capella group The Madhatters took the stage. The Madhatters are a rotating group of Wisconsin college guys who clearly just joined the group to meet girls, and sing the kind of Boys II Men songs that have been out of style since...Boys II Men. None of them can sing worth a lick, which is why they crowd a dozen of them onto the stage, all wailing at once like wounded dogs, one of them carrying a Mad Hatter's hat, bearing it in his hands as though it were some Masonic holy device that would grant them approval from the audience. One of their last songs, to contribute to the mood of the evening, was about a man who walks in on his ex-girlfriend while she's taking a shower, and proceeds to spy on her from the dark. Good job, guys.

Finally the Cherry Pop Burlesque returned, and I'd never been so happy to see them, although there audible groans from parents in the audience. It was the door-prize portion of the evening. We checked our raffle tickets, and a lucky girl who looked to be all of 15 won a free pass to an evening with the Cherry Pop Burlesque. (The first time I attended Duck Soup, a boy of eight or nine won tickets to Late Night Catechism, so this seemed appropriate.)

As for the film? Well, it was Safety Last!, my favorite Harold Lloyd film, the one where he dangles from the clock above the city. But that's almost beside the point. I'd seen the film before, and what stuck with me more was the moment in Jazzworks when one of the dancers dropped her feather boa; to pick it up again would ruin the choreography, so she kept dancing while pretending to twirl the invisible boa through the air. Sublime.

This Saturday's Duck Soup, coming a month later, featured three Charlie Chaplin shorts. There was to be four, but the fourth, "The Immigrant," arrived with a reel missing, so it wasn't shown; still this left about 80 minutes of Mutual Studio shorts to screen: "The Rink," in which Chaplin gracefully rollerskates through the spreading chaos he creates; "Easy Street," in which Chaplin becomes a cop and matches wits with a thug; and "Behind the Screen," a parody of the making of silent films.

Olive Talique was back, this time co-hosting with Duck Soup stalwart Joe Thompson. They were playing George and Gracie, as Talique admitted in an interview with Madison's weekly paper The Isthmus, and this seems appropriate, since the curly-haired Thompson is always a pleasing throwback to the style of comedy practiced by Jack Benny and Groucho and other comedians from yesterday. Aside from Talique's appearance, there were fewer moments of scandal this time around. Sure, the juggler known as The Truly Remarkable Loon kept dropping his props, but the audience loved it. And then there was the moment when the entire Cherry Pop Burlesque suddenly reappeared on the stage, with the Cherry Pop emcee (who looks a lot like John Waters) encouraging the older members of the audience to come to the Overture Cherry Pop show, which will promise much to those who "admire the female form." Oh, and then there were the shorts themselves; who could remember that in "Easy Street," Chaplin accidentally sits on a doper's needle and becomes rejuvenated so that he can defeat his enemies? (Just like real heroin!) Or that in "Behind the Screen," Chaplin is in one scene mistaken for a homosexual, and basically derided as a fairy by his co-worker? (It's a silent film, but the gestures scream "fairy.") It was a sound message to the parents in the audience--you can't hide your kids from indecency, not even in the old, black-and-white films. There's an ongoing myth in American culture right now that our society has become so decayed that it's imperative we try to return to a purer, more moralistic time. When even Chaplin is refusing to succumb to santization, I guess you either keep your kids' noses buried in the Dick and Jane books, or you head on out to discover the joyful hedonism of the Cherry Pop Burlesque. One or the other, take your pick. There was a kid--of eight or nine--who was giggling madly at everything Charlie Chaplin did (these films are from 1916!), so I think, for that kid if not that family, the evening was worth the risks.

Olive Talique was back, this time co-hosting with Duck Soup stalwart Joe Thompson. They were playing George and Gracie, as Talique admitted in an interview with Madison's weekly paper The Isthmus, and this seems appropriate, since the curly-haired Thompson is always a pleasing throwback to the style of comedy practiced by Jack Benny and Groucho and other comedians from yesterday. Aside from Talique's appearance, there were fewer moments of scandal this time around. Sure, the juggler known as The Truly Remarkable Loon kept dropping his props, but the audience loved it. And then there was the moment when the entire Cherry Pop Burlesque suddenly reappeared on the stage, with the Cherry Pop emcee (who looks a lot like John Waters) encouraging the older members of the audience to come to the Overture Cherry Pop show, which will promise much to those who "admire the female form." Oh, and then there were the shorts themselves; who could remember that in "Easy Street," Chaplin accidentally sits on a doper's needle and becomes rejuvenated so that he can defeat his enemies? (Just like real heroin!) Or that in "Behind the Screen," Chaplin is in one scene mistaken for a homosexual, and basically derided as a fairy by his co-worker? (It's a silent film, but the gestures scream "fairy.") It was a sound message to the parents in the audience--you can't hide your kids from indecency, not even in the old, black-and-white films. There's an ongoing myth in American culture right now that our society has become so decayed that it's imperative we try to return to a purer, more moralistic time. When even Chaplin is refusing to succumb to santization, I guess you either keep your kids' noses buried in the Dick and Jane books, or you head on out to discover the joyful hedonism of the Cherry Pop Burlesque. One or the other, take your pick. There was a kid--of eight or nine--who was giggling madly at everything Charlie Chaplin did (these films are from 1916!), so I think, for that kid if not that family, the evening was worth the risks.