Return of the Jedi (1983). Although my parents insist they took me to The Empire Strikes Back, I don't remember it. My first memory of seeing a Star Wars movie in a theater is the opening night of Return of the Jedi. I learn from IMDB that the release date was May 25, 1983, so I would have been 6 years old. When you're an elementary school kid--I think they still do this--Scholastic holds book fairs at your school, and a month or so before that you get to order books out of something like a 6-page catalog printed on colorful newspaper, the receiving of which was always a major highlight in my young life. I went crazy when I saw that at the next book fair was going to be "Revenge of the Jedi: The Storybook." I asked my parents. They said yes. When I got the book, I memorized every page, and scrutinized the photos as though they were frames of the Zapruder film. (What on earth was that weird alien with the really long face in Jabba's Palace? Could that be Jabba? No, as it turns out--Jabba was a giant slug.) It was a family night out when we attended the film's opening in or near Union City, California, and the line wrapped around the theater. But this was California in May, so it was beautiful. While my parents held our place in line, my sister and I ran to the back of the theater where we placed our ears against the wall. We could hear the speeder bike chase through the forests of Endor--as I explained to my sister, who had not read the storybook (nor had much interest). Zzzhooum, zzzhoumm, zzzhoum. Listening to the bikes race with the pictures still held in my imagination was almost as exciting as seeing the film an hour later. Though not quite.

Return of the Jedi (1983). Although my parents insist they took me to The Empire Strikes Back, I don't remember it. My first memory of seeing a Star Wars movie in a theater is the opening night of Return of the Jedi. I learn from IMDB that the release date was May 25, 1983, so I would have been 6 years old. When you're an elementary school kid--I think they still do this--Scholastic holds book fairs at your school, and a month or so before that you get to order books out of something like a 6-page catalog printed on colorful newspaper, the receiving of which was always a major highlight in my young life. I went crazy when I saw that at the next book fair was going to be "Revenge of the Jedi: The Storybook." I asked my parents. They said yes. When I got the book, I memorized every page, and scrutinized the photos as though they were frames of the Zapruder film. (What on earth was that weird alien with the really long face in Jabba's Palace? Could that be Jabba? No, as it turns out--Jabba was a giant slug.) It was a family night out when we attended the film's opening in or near Union City, California, and the line wrapped around the theater. But this was California in May, so it was beautiful. While my parents held our place in line, my sister and I ran to the back of the theater where we placed our ears against the wall. We could hear the speeder bike chase through the forests of Endor--as I explained to my sister, who had not read the storybook (nor had much interest). Zzzhooum, zzzhoumm, zzzhoum. Listening to the bikes race with the pictures still held in my imagination was almost as exciting as seeing the film an hour later. Though not quite. Hercules (1983). No, this isn't the Steve Reeves film, but the Lou Ferrigno Italian production which was released dubbed in the United States circa '83. My dad took me to the local drive-in to see it, as he saw the Reeves film when he was a kid and it made a big impression on him. Also, perhaps, because he liked the Hulk show. I have a few great drive-in memories, which I'm now holding onto desperately like some old nostalgic coot as drive-ins begin to disappear from the American landscape. None of the movies I saw there were any good: The Karate Kid Part II and Iron Eagles II are the others I remember, and Hercules was probably the worst of them. But I usually wasn't watching the movies our car was pointed at; I was sneaking glimpses of the other screens that formed a circle around the main lot, trying to see if any of them were R-rated (one of the Poltergeist sequels I kept a close eye on). I actually remember nothing about Hercules, except that it was strange and I couldn't follow it. When I asked my dad about it many years later, he said, "That was awful." I don't have the heart to tell him that the Reeves Hercules has appeared on Mystery Science Theater 3000.

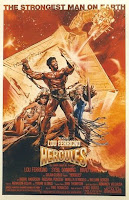

Hercules (1983). No, this isn't the Steve Reeves film, but the Lou Ferrigno Italian production which was released dubbed in the United States circa '83. My dad took me to the local drive-in to see it, as he saw the Reeves film when he was a kid and it made a big impression on him. Also, perhaps, because he liked the Hulk show. I have a few great drive-in memories, which I'm now holding onto desperately like some old nostalgic coot as drive-ins begin to disappear from the American landscape. None of the movies I saw there were any good: The Karate Kid Part II and Iron Eagles II are the others I remember, and Hercules was probably the worst of them. But I usually wasn't watching the movies our car was pointed at; I was sneaking glimpses of the other screens that formed a circle around the main lot, trying to see if any of them were R-rated (one of the Poltergeist sequels I kept a close eye on). I actually remember nothing about Hercules, except that it was strange and I couldn't follow it. When I asked my dad about it many years later, he said, "That was awful." I don't have the heart to tell him that the Reeves Hercules has appeared on Mystery Science Theater 3000..jpg) Jaws 3-D (1983). What a good year! I also saw this terrible Jaws sequel. I hadn't seen the first two, and I have no idea why my dad thought it was a good idea to take me to one. All I knew about Jaws came from a recent trip to Universal Studios California (that was the only Universal Studios theme park back then). Jaws had attacked our tour bus and freaked me out, I knew that much. And there was that scary poster of the first film which was all over the theme park: a dinosaur-sized shark launching like a missile up at the tiny figure of a bikini-clad innocent. This film scared the hell out of me, particularly the opening credit sequence, in which a fish is caught in a maelstrom of underwater froth and blood, and gets sliced in half, the front half still swimming IN THREE-DEE toward the viewer. That was highly disturbing for me. Also disturbing--but thrilling in a way--was the 3-D trailer which preceded the film: the post-apocalyptic B-movie Metalstorm: The Destruction of Jared-Syn. A spiked metal ball was hurtled at the viewer. It gave me nightmares for weeks, so naturally I rented it on VHS the first chance I got and watched it repeatedly.

Jaws 3-D (1983). What a good year! I also saw this terrible Jaws sequel. I hadn't seen the first two, and I have no idea why my dad thought it was a good idea to take me to one. All I knew about Jaws came from a recent trip to Universal Studios California (that was the only Universal Studios theme park back then). Jaws had attacked our tour bus and freaked me out, I knew that much. And there was that scary poster of the first film which was all over the theme park: a dinosaur-sized shark launching like a missile up at the tiny figure of a bikini-clad innocent. This film scared the hell out of me, particularly the opening credit sequence, in which a fish is caught in a maelstrom of underwater froth and blood, and gets sliced in half, the front half still swimming IN THREE-DEE toward the viewer. That was highly disturbing for me. Also disturbing--but thrilling in a way--was the 3-D trailer which preceded the film: the post-apocalyptic B-movie Metalstorm: The Destruction of Jared-Syn. A spiked metal ball was hurtled at the viewer. It gave me nightmares for weeks, so naturally I rented it on VHS the first chance I got and watched it repeatedly. Jurassic Park/Schindler's List (1993). It's easy to forget now, but when Jurassic Park first opened, the excitement over the groundbreaking special effects was akin to first seeing King Kong in 1933. Yes, there had been CG effects before, but nothing like the dinosaurs in Jurassic Park, which actually looked like real, breathing creatures. It helped considerably that the CG was augmented by Stan Winston's animatronic dinos, which gave an extra sense of realism; most viewers couldn't tell the difference between the CG and the real, tactile robots, so smoothly did the two effects blend, although it would seem more transparent now, I imagine. Complaints about the script came later--to see this film on opening night was like being caught in the middle of an electrical storm. We were all very tense and full of wonder, and it was a rare experience. I took my mom a week later and she said that she lost ten pounds watching it. 1993 was Steven Spielberg's comeback year. After proving he could still make a Jaws-styled thrill ride with Jurassic Park, he made the Oscar-winner Schindler's List, which has (unfortunately) fallen out of favor with many critics over the years, but was pretty widely acclaimed at the time. My memory of seeing this in the theater is dominated by my sensory memory of aching hunger, because for whatever reason I hadn't eaten that day (or had eaten very little), so the three hours of the film were spent in a physical discomfort that only accentuated the viewing experience. This effect undoubtedly contributed to the fact that Schindler's List was an extremely important movie for me in my high school years, one of those "gateway" films that led to seeing more arty kinds of pictures. (The Seven Samurai and High and Low, two Akira Kurosawa films which I watched on video around the same time, were two major gateway films for me, opening my eyes to what film could be; Orson Welles' The Trial was another.)

Jurassic Park/Schindler's List (1993). It's easy to forget now, but when Jurassic Park first opened, the excitement over the groundbreaking special effects was akin to first seeing King Kong in 1933. Yes, there had been CG effects before, but nothing like the dinosaurs in Jurassic Park, which actually looked like real, breathing creatures. It helped considerably that the CG was augmented by Stan Winston's animatronic dinos, which gave an extra sense of realism; most viewers couldn't tell the difference between the CG and the real, tactile robots, so smoothly did the two effects blend, although it would seem more transparent now, I imagine. Complaints about the script came later--to see this film on opening night was like being caught in the middle of an electrical storm. We were all very tense and full of wonder, and it was a rare experience. I took my mom a week later and she said that she lost ten pounds watching it. 1993 was Steven Spielberg's comeback year. After proving he could still make a Jaws-styled thrill ride with Jurassic Park, he made the Oscar-winner Schindler's List, which has (unfortunately) fallen out of favor with many critics over the years, but was pretty widely acclaimed at the time. My memory of seeing this in the theater is dominated by my sensory memory of aching hunger, because for whatever reason I hadn't eaten that day (or had eaten very little), so the three hours of the film were spent in a physical discomfort that only accentuated the viewing experience. This effect undoubtedly contributed to the fact that Schindler's List was an extremely important movie for me in my high school years, one of those "gateway" films that led to seeing more arty kinds of pictures. (The Seven Samurai and High and Low, two Akira Kurosawa films which I watched on video around the same time, were two major gateway films for me, opening my eyes to what film could be; Orson Welles' The Trial was another.) 12 Monkeys (1995). This one's hard to explain--most of all to myself. About a month before I saw it, I watched Vertigo for the first time. It was an odd viewing, because I was at a friend's house and he invited some girls over, and we had two films we'd rented--Vertigo, which I'd chosen (what a dork), and some slasher film which he chose. The slasher film was terrible, but the girls thought it was better. They were bored to death by Vertigo. At one point during one of the films, his two cats raced in a circle around the room, and used my face as part of their racetrack. So I was bleeding out of my face at one point. It was a weird night, but I thought Vertigo was pretty interesting; I had a particular since of deja vu watching it because I grew up around many of the film's Bay Area locations, and visited, as a child, the mission which is so pivotal in the plot. But the film is all about deja vu and strange feelings of familiarity. If you've seen 12 Monkeys you might know the connection: at one point, Bruce Willis and Madeleine Stowe hide in a theater showing a Hitchcock retrospective. The scene from Vertigo where Kim Novak points at the exposed tree trunk--its rings marking historic moments of the past--she notes that in those rings, her entire lifespan is so minor as to be insignificant. In the next scene, Stowe puts on a wig Willis gave her--a blonde wig, like Novak's in the film--and he is instantly struck with deja-vu (critical to 12 Monkeys' plot), which is accompanied by Bernard Hermann's theme to Vertigo rising on the soundtrack. The effect this synchronicity had on me in the theater was a physical and mental sensation I've rarely felt. It was sort of like all of these strands of time and space in my life had woven together, knotted themselves briefly, and then unbound themselves and flitted to their distant corners again. I don't know why. But I still have that traces of that curious feeling each time I watch Vertigo, which has now become one of my favorite films. Something tells me it should be the film I watch before I die, possibly right after Kim Novak's long finger moves away from the severed tree. If one gets to pick such things.

12 Monkeys (1995). This one's hard to explain--most of all to myself. About a month before I saw it, I watched Vertigo for the first time. It was an odd viewing, because I was at a friend's house and he invited some girls over, and we had two films we'd rented--Vertigo, which I'd chosen (what a dork), and some slasher film which he chose. The slasher film was terrible, but the girls thought it was better. They were bored to death by Vertigo. At one point during one of the films, his two cats raced in a circle around the room, and used my face as part of their racetrack. So I was bleeding out of my face at one point. It was a weird night, but I thought Vertigo was pretty interesting; I had a particular since of deja vu watching it because I grew up around many of the film's Bay Area locations, and visited, as a child, the mission which is so pivotal in the plot. But the film is all about deja vu and strange feelings of familiarity. If you've seen 12 Monkeys you might know the connection: at one point, Bruce Willis and Madeleine Stowe hide in a theater showing a Hitchcock retrospective. The scene from Vertigo where Kim Novak points at the exposed tree trunk--its rings marking historic moments of the past--she notes that in those rings, her entire lifespan is so minor as to be insignificant. In the next scene, Stowe puts on a wig Willis gave her--a blonde wig, like Novak's in the film--and he is instantly struck with deja-vu (critical to 12 Monkeys' plot), which is accompanied by Bernard Hermann's theme to Vertigo rising on the soundtrack. The effect this synchronicity had on me in the theater was a physical and mental sensation I've rarely felt. It was sort of like all of these strands of time and space in my life had woven together, knotted themselves briefly, and then unbound themselves and flitted to their distant corners again. I don't know why. But I still have that traces of that curious feeling each time I watch Vertigo, which has now become one of my favorite films. Something tells me it should be the film I watch before I die, possibly right after Kim Novak's long finger moves away from the severed tree. If one gets to pick such things. Citizen Kane/The Third Man (1941/1949, screened in 1999). Before I moved out to Seattle for grad school, my aunt, who lived in Washington, found an apartment for me. It was tiny, and the window was too high to comfortably look out from, and the closet space was completely taken up by a water heater, and someone kept dropping used condoms around my car in the parking lot below, but there were two really great selling points she couldn't have known about. One is that I was only a few blocks away from the best video store on the planet, Scarecrow Video. The other is that I was even closer to a number of theaters, one of which had a spectacular art house and revival program. Friendless, new to the city, I would frequently walk up and down the main drag by the university on any given afternoon, looking for something to do; wandering into the theater was always a good option. It was here that I first saw Citizen Kane, priding myself very self-consciously that my first viewing would be on the big screen. I haven't seen it since--I've been meaning to get around to that--but I still have very vivid memories of Welles' camera snaking through the passages of Xanadu in search of the ghost of Charles Foster Kane. In the same theater I saw The Third Man for the first time--which I have, happily, revisited. I was particularly haunted by the final scene, the long, unrequited shot, and the Anton Karas music, which followed me on my walk home. I was captivated by the film, mostly because it was not what I was expecting. Because of The Maltese Falcon, I had a skewed vision of what film noir was, and this was my full immersion into the real deal. It was a sad, bleak, but thrilling film, great in unexpected ways.

Citizen Kane/The Third Man (1941/1949, screened in 1999). Before I moved out to Seattle for grad school, my aunt, who lived in Washington, found an apartment for me. It was tiny, and the window was too high to comfortably look out from, and the closet space was completely taken up by a water heater, and someone kept dropping used condoms around my car in the parking lot below, but there were two really great selling points she couldn't have known about. One is that I was only a few blocks away from the best video store on the planet, Scarecrow Video. The other is that I was even closer to a number of theaters, one of which had a spectacular art house and revival program. Friendless, new to the city, I would frequently walk up and down the main drag by the university on any given afternoon, looking for something to do; wandering into the theater was always a good option. It was here that I first saw Citizen Kane, priding myself very self-consciously that my first viewing would be on the big screen. I haven't seen it since--I've been meaning to get around to that--but I still have very vivid memories of Welles' camera snaking through the passages of Xanadu in search of the ghost of Charles Foster Kane. In the same theater I saw The Third Man for the first time--which I have, happily, revisited. I was particularly haunted by the final scene, the long, unrequited shot, and the Anton Karas music, which followed me on my walk home. I was captivated by the film, mostly because it was not what I was expecting. Because of The Maltese Falcon, I had a skewed vision of what film noir was, and this was my full immersion into the real deal. It was a sad, bleak, but thrilling film, great in unexpected ways. Blade Runner: The Workprint/Brazil: The Director's Cut (1982/1985, viewed in 1999). These were my two favorite movies around this time. Both of them played in rarified bootleg prints at a different theater in Seattle, I think the Neptune, although to check that out would be to do research, which is taking the fun out of this memory game. The theater had the naughty habit of showing alternate prints of films which they really had no legal right to screen. It was exciting to see the director's cut of Brazil because the Gilliam cut hadn't yet been released on DVD by Criterion (though that would happen shortly). It was a bleaker, more subversive film, and there was eager applause when the theater manager introduced it as "something you've never seen before." But that was nothing compared to the applause which greeted that same statement before Blade Runner. To a larger house, the cult science fiction film--a flop in its day, but now considered one of the great SF films of all time--unspooled in "workprint" form, which means it contained scenes that would later be trimmed, an alternate opening title, and a temporary soundtrack with cues from other films (sometimes recognizable). Like the Director's Cut of the early 90's, Harrison Ford's narration was gone, but at its longer running time the film was more textured and grim. There's an excellent book, Future Noir, which chronicles all the various cuts of Blade Runner, including this one, but some of the clandestine fun will be taken out of this memory when the workprint is (reportedly) released on DVD later this year, along with a new cut of the film. I remember thinking as I watched it: Thank the good Lord I'm living in Seattle.

Blade Runner: The Workprint/Brazil: The Director's Cut (1982/1985, viewed in 1999). These were my two favorite movies around this time. Both of them played in rarified bootleg prints at a different theater in Seattle, I think the Neptune, although to check that out would be to do research, which is taking the fun out of this memory game. The theater had the naughty habit of showing alternate prints of films which they really had no legal right to screen. It was exciting to see the director's cut of Brazil because the Gilliam cut hadn't yet been released on DVD by Criterion (though that would happen shortly). It was a bleaker, more subversive film, and there was eager applause when the theater manager introduced it as "something you've never seen before." But that was nothing compared to the applause which greeted that same statement before Blade Runner. To a larger house, the cult science fiction film--a flop in its day, but now considered one of the great SF films of all time--unspooled in "workprint" form, which means it contained scenes that would later be trimmed, an alternate opening title, and a temporary soundtrack with cues from other films (sometimes recognizable). Like the Director's Cut of the early 90's, Harrison Ford's narration was gone, but at its longer running time the film was more textured and grim. There's an excellent book, Future Noir, which chronicles all the various cuts of Blade Runner, including this one, but some of the clandestine fun will be taken out of this memory when the workprint is (reportedly) released on DVD later this year, along with a new cut of the film. I remember thinking as I watched it: Thank the good Lord I'm living in Seattle. The Saragossa Manuscript (1965, visited in 1999). I was taking a course called Orientalism, which, as I've said before on this blog, changed my life, because it introduced me to the Arabian Nights. The Saragossa Manuscript, which I saw in a revival screening in Seattle that year, had as big an effect on me. Like the Nights, it was a film of stories-within-stories (based, rather faithfully, on the long Jan Potocki novel of the early 19th century). It was witty, it was absorbing, it was playful, it was dangerous, and it paid off in surreal moments of transcendence. I caught this, I think, on the last night it played its Seattle run, and thought myself grateful that I'd taken a chance on it. It remains one of my favorite films.

The Saragossa Manuscript (1965, visited in 1999). I was taking a course called Orientalism, which, as I've said before on this blog, changed my life, because it introduced me to the Arabian Nights. The Saragossa Manuscript, which I saw in a revival screening in Seattle that year, had as big an effect on me. Like the Nights, it was a film of stories-within-stories (based, rather faithfully, on the long Jan Potocki novel of the early 19th century). It was witty, it was absorbing, it was playful, it was dangerous, and it paid off in surreal moments of transcendence. I caught this, I think, on the last night it played its Seattle run, and thought myself grateful that I'd taken a chance on it. It remains one of my favorite films. The Blair Witch Project (1999). Before the film began, the theater owners played an ambient soundtrack of nocturnal, woodsy effects, to make it sound like we were in a campsite late at night. It really creeped everyone out. This was right before the film opened wide in the U.S., and was just playing a few theaters, including Seattle, so the hype was just building and no one really knew what the movie was about. After it was over, people were freaked out. It's hard to explain that now, since the movie--after an ill-advised attempt to make a franchise out of it--has gone out of fashion.

The Blair Witch Project (1999). Before the film began, the theater owners played an ambient soundtrack of nocturnal, woodsy effects, to make it sound like we were in a campsite late at night. It really creeped everyone out. This was right before the film opened wide in the U.S., and was just playing a few theaters, including Seattle, so the hype was just building and no one really knew what the movie was about. After it was over, people were freaked out. It's hard to explain that now, since the movie--after an ill-advised attempt to make a franchise out of it--has gone out of fashion. Yellow Submarine (1968, restored and revisited in 2000). It played the same theater where I saw Blade Runner and Brazil, but it wasn't a bootleg: this was the official, much ballyhooed restoration of the Beatles classic, with a new "Hey Bulldog" scene added in (well, new to American audiences, as it was standard for the British version). I was happy to take my visiting fiancee to this, as we practically met over the movie. I remember two aging hippes sitting behind us: one said, "Man, I got some stuff in the car. We should smoke a few." Or something like that. After "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds," there was applause. And there were little kids in the front row who knew the film and were dancing.

Yellow Submarine (1968, restored and revisited in 2000). It played the same theater where I saw Blade Runner and Brazil, but it wasn't a bootleg: this was the official, much ballyhooed restoration of the Beatles classic, with a new "Hey Bulldog" scene added in (well, new to American audiences, as it was standard for the British version). I was happy to take my visiting fiancee to this, as we practically met over the movie. I remember two aging hippes sitting behind us: one said, "Man, I got some stuff in the car. We should smoke a few." Or something like that. After "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds," there was applause. And there were little kids in the front row who knew the film and were dancing. Faith Hubley Animation (various years, culminating in 2000 retrospective). This was the first Sundance Film Festival I attended. I was visiting my fiancee, who lived in Salt Lake City. The premiere of Chuck and Buck was the first we saw, but what really seems special these years later is the retrospective of animation by Faith Hubley, wife of animator John Hubley (who had worked on many of the classic Disney films, and later became an important figure in independent animation). Faith was there in attendance, and screened a wide variety of films, including some she had made with her daughter. She answered questions and was delighted to discuss her collaborations with Miles Davis. My wife and I can probably claim this event as sparking a greater interest and curiosity in animation, but the memory is particularly poignant because Faith died of cancer the following year.

Faith Hubley Animation (various years, culminating in 2000 retrospective). This was the first Sundance Film Festival I attended. I was visiting my fiancee, who lived in Salt Lake City. The premiere of Chuck and Buck was the first we saw, but what really seems special these years later is the retrospective of animation by Faith Hubley, wife of animator John Hubley (who had worked on many of the classic Disney films, and later became an important figure in independent animation). Faith was there in attendance, and screened a wide variety of films, including some she had made with her daughter. She answered questions and was delighted to discuss her collaborations with Miles Davis. My wife and I can probably claim this event as sparking a greater interest and curiosity in animation, but the memory is particularly poignant because Faith died of cancer the following year. Waking Life (2001). Every year we lived in Utah we went to the Sundance Film Festival, and each year suffered the usual pangs of regret at not having caught whatever the big films that year were--as though it were possible to have that kind of precognition. For example, in retrospect I would've liked to have attended the Hedwig and the Angry Inch premiere, but you have to understand that when you read a short blurb about that kind of film in the Sundance preview guide you know it will be either brilliant or awful. Waking Life was another film that could have gone either way, and I credit my wife for talking me into it. A feature length animated film consisting of philosphical discussions? That could be pretty bad. But I hadn't seen Slacker at that point, Richard Linklater's dry-run for this film, and didn't know of what he was capable. The premiere took place in the best of Sundance's venues, the Eccles Theatre, a very large auditorium which the high school uses through most of the year. Before the film, Linklater took the stage and announced that he had only previewed the completed version of the film earlier that day; visibly nervous, he stammered out that the film might work better for the audience if we were all on drugs. Then started the rough cut of Waking Life, pretty much identical to the final version (minus ending credits). The animation, a new, kaleidoscopic rotoscoping technique which enhanced the film's dream-like narrative, was like nothing any of us had ever seen (it's since been used in commercials and in Linklater's own A Scanner Darkly). The meandering conversations were whimsical, smart, and occasionally very moving. Waking Life was extraordinary. The Eccles audience gave a rare standing ovation, and Linklater seemed overwhelmed; although it should be noted that the army of animators had reserved the first several rows, and were as overjoyed as everyone else. This is what I consider to be the ideal Sundance experience: the little guy makes a sincere gem of a film, like nothing you've ever seen, and despite all his risks, it all pays off with this beautiful outpouring of adulation. When I think of Sundance, I like to think of this night, and not all those others--not the woman on the bus vomiting on my wife's feet, or Courtney Love running out through the emergency exit multiple times during the premiere of Julie Johnson presumably so she could take a few hits of something, or all the obnoxious people from L.A. with copies of Variety clutched in their hands while they spread gossip about the local celeb parties.

Waking Life (2001). Every year we lived in Utah we went to the Sundance Film Festival, and each year suffered the usual pangs of regret at not having caught whatever the big films that year were--as though it were possible to have that kind of precognition. For example, in retrospect I would've liked to have attended the Hedwig and the Angry Inch premiere, but you have to understand that when you read a short blurb about that kind of film in the Sundance preview guide you know it will be either brilliant or awful. Waking Life was another film that could have gone either way, and I credit my wife for talking me into it. A feature length animated film consisting of philosphical discussions? That could be pretty bad. But I hadn't seen Slacker at that point, Richard Linklater's dry-run for this film, and didn't know of what he was capable. The premiere took place in the best of Sundance's venues, the Eccles Theatre, a very large auditorium which the high school uses through most of the year. Before the film, Linklater took the stage and announced that he had only previewed the completed version of the film earlier that day; visibly nervous, he stammered out that the film might work better for the audience if we were all on drugs. Then started the rough cut of Waking Life, pretty much identical to the final version (minus ending credits). The animation, a new, kaleidoscopic rotoscoping technique which enhanced the film's dream-like narrative, was like nothing any of us had ever seen (it's since been used in commercials and in Linklater's own A Scanner Darkly). The meandering conversations were whimsical, smart, and occasionally very moving. Waking Life was extraordinary. The Eccles audience gave a rare standing ovation, and Linklater seemed overwhelmed; although it should be noted that the army of animators had reserved the first several rows, and were as overjoyed as everyone else. This is what I consider to be the ideal Sundance experience: the little guy makes a sincere gem of a film, like nothing you've ever seen, and despite all his risks, it all pays off with this beautiful outpouring of adulation. When I think of Sundance, I like to think of this night, and not all those others--not the woman on the bus vomiting on my wife's feet, or Courtney Love running out through the emergency exit multiple times during the premiere of Julie Johnson presumably so she could take a few hits of something, or all the obnoxious people from L.A. with copies of Variety clutched in their hands while they spread gossip about the local celeb parties. Suspiria (1977, but for the first time in 2001 or so). This topic started with Grindhouse, but the most authentic grindhouse experience I've ever had, which Tarantino and Rodriguez's film so carefully evokes, was attending a revival theater in SLC for a midnight screening of this Dario Argento classic. It's key that I'd never seen it before, and also key that the film was very, very beaten up, and the soundtrack of such a low fidelity that they had to crank it up very, very high, creating a kind of screeching effect that kept your nerves on edge. The opening murder sequence, with its delirious, sweeping camera movements and vivid blues and reds, culminating in the close-up penetration of a pumping heart, was one of the most visceral experiences I've had in a theater. Just delightful. This may have been when Anne swore off horror movies.

Suspiria (1977, but for the first time in 2001 or so). This topic started with Grindhouse, but the most authentic grindhouse experience I've ever had, which Tarantino and Rodriguez's film so carefully evokes, was attending a revival theater in SLC for a midnight screening of this Dario Argento classic. It's key that I'd never seen it before, and also key that the film was very, very beaten up, and the soundtrack of such a low fidelity that they had to crank it up very, very high, creating a kind of screeching effect that kept your nerves on edge. The opening murder sequence, with its delirious, sweeping camera movements and vivid blues and reds, culminating in the close-up penetration of a pumping heart, was one of the most visceral experiences I've had in a theater. Just delightful. This may have been when Anne swore off horror movies. The Thief of Bagdad (1924, dusted off in 2001 or '02). If you're ever in SLC you should visit a place just a little ways south of the downtown called the Organ Loft. Most nights it's a banquet hall rented out for wedding receptions and parties, but it has a seasonal program of silent films with live organ accompaniment. The organ is really something: called the Mighty Wurlitzer, it's a pretty impressive instrument that actually did accompany silent films in the 20's; now it's hooked up to pipes that completely envelop you in the hall, as you sit on one of the fairly uncomfortable chairs they bring out into the middle of the dance floor. Before each film you receive a brief introduction to set the film in context, and then the sound of the organ rattles your chair and lifts you up and tugs you straight into the heart of the film. We saw The Phantom of the Opera this way first--an Organ Loft Halloween tradition--and then West of Zanzibar, also with Lon Chaney, and Nosferatu. My favorite was, of course, The Thief of Bagdad, a veritable epic with a flying carpet and a winged horse and a giant spider and those amazing sets by William Cameron Menzies, which look like Dr. Seuss illustrations. The Organ Loft gets an older clientele--mostly senior citizens, actually--but we went as film buffs. I would leave the theater and wonder why anyone my age would want to do something else with their Friday night.

The Thief of Bagdad (1924, dusted off in 2001 or '02). If you're ever in SLC you should visit a place just a little ways south of the downtown called the Organ Loft. Most nights it's a banquet hall rented out for wedding receptions and parties, but it has a seasonal program of silent films with live organ accompaniment. The organ is really something: called the Mighty Wurlitzer, it's a pretty impressive instrument that actually did accompany silent films in the 20's; now it's hooked up to pipes that completely envelop you in the hall, as you sit on one of the fairly uncomfortable chairs they bring out into the middle of the dance floor. Before each film you receive a brief introduction to set the film in context, and then the sound of the organ rattles your chair and lifts you up and tugs you straight into the heart of the film. We saw The Phantom of the Opera this way first--an Organ Loft Halloween tradition--and then West of Zanzibar, also with Lon Chaney, and Nosferatu. My favorite was, of course, The Thief of Bagdad, a veritable epic with a flying carpet and a winged horse and a giant spider and those amazing sets by William Cameron Menzies, which look like Dr. Seuss illustrations. The Organ Loft gets an older clientele--mostly senior citizens, actually--but we went as film buffs. I would leave the theater and wonder why anyone my age would want to do something else with their Friday night. Lawrence of Arabia (1962, but only at Ebertfest in 2004). When we moved to Madison, we lost the chance to go to Sundance and took as substitute two smaller film festivals: the Wisconsin Film Festival (which is quickly growing) and Roger Ebert's Overlooked Film Festival (the most recent of which occurred this past weekend, though we couldn't attend this year). Ebert's festival takes place in Champaign-Urbana, Illinois, with a selection of older films that he deems worthy of a larger audience--though his opening night film is usually a widescreen classic. We arrived a little late for 2004's widescreen epic, Lawrence of Arabia, and a line was already stretching around the theater. This meant we had to grab whatever open seats we could find, and these were in the corner of the front row of the balcony. Actually spectacular seats for Lawrence of Arabia, even though there was really no leg room and I couldn't walk after the film. I'd seen it before, but it had minimal impact, because I was too young. But at Ebertfest it completely arrested my attention, and I had no qualms in declaring it one of the greatest films I'd ever seen. It helped that it was projected in 70mm, on an immense screen and personally supervised by Robert A. Harris, who had restored the film under the advice of David Lean. After Ebert introduced the film with none other than controversial MPAA president Jack Valenti--deceased just this past week--who was booed and cheered at once by the conflicted audience, a blissful 228 minutes passed. Harris then joined Ebert onstage with the film's editor, Anne Coates, who excitedly discussed cutting the film with Mr. Lean. I contend this was my greatest filmgoing experience ever: a spectacular film, presented in a spectacular fashion, followed by a deeply engaging conversation steeped in film history. Almost topped a few days later by...

Lawrence of Arabia (1962, but only at Ebertfest in 2004). When we moved to Madison, we lost the chance to go to Sundance and took as substitute two smaller film festivals: the Wisconsin Film Festival (which is quickly growing) and Roger Ebert's Overlooked Film Festival (the most recent of which occurred this past weekend, though we couldn't attend this year). Ebert's festival takes place in Champaign-Urbana, Illinois, with a selection of older films that he deems worthy of a larger audience--though his opening night film is usually a widescreen classic. We arrived a little late for 2004's widescreen epic, Lawrence of Arabia, and a line was already stretching around the theater. This meant we had to grab whatever open seats we could find, and these were in the corner of the front row of the balcony. Actually spectacular seats for Lawrence of Arabia, even though there was really no leg room and I couldn't walk after the film. I'd seen it before, but it had minimal impact, because I was too young. But at Ebertfest it completely arrested my attention, and I had no qualms in declaring it one of the greatest films I'd ever seen. It helped that it was projected in 70mm, on an immense screen and personally supervised by Robert A. Harris, who had restored the film under the advice of David Lean. After Ebert introduced the film with none other than controversial MPAA president Jack Valenti--deceased just this past week--who was booed and cheered at once by the conflicted audience, a blissful 228 minutes passed. Harris then joined Ebert onstage with the film's editor, Anne Coates, who excitedly discussed cutting the film with Mr. Lean. I contend this was my greatest filmgoing experience ever: a spectacular film, presented in a spectacular fashion, followed by a deeply engaging conversation steeped in film history. Almost topped a few days later by... Gates of Heaven/Invincible (1980/2001, at Ebertfest in 2004). Errol Morris was presenting his modest 1980 documentary about a pet cemetery, which Ebert has long declared one of the best films ever made, and with him was Werner Herzog, director of Invincible, which was scheduled for a screening later that day. Back in the late 70's, Morris had told his friend Herzog he was going to make a movie, and Herzog replied that if Morris ever made a movie, he'd eat his shoe. Sure enough, Gates of Heaven was inexplicably produced, and Herzog appeared in a short film shot by Les Blank entitled "Werner Herzog Eats His Shoe." It was exactly what it claimed to be. After Gates of Heaven screened, a giddy Morris--who had just won his first Oscar, for Fog of War--sparred with the audience during a Q&A, answering questions with either glib jokes or stunning anecdotes. I still remember what he said regarding his interview technique, and have quoted it often: "If you let anyone talk long enough, eventually they will prove themselves to be completely crazy." There was a film screened between Gates of Heaven and Invincible, but it wasn't very good, so let's skip straight to the Herzog. Invincible is good, and definitely overlooked, but what sticks with me most is his extended Q&A afterward. It was getting very late, so most of the theater left, but those who stayed were treated to a typically astounding Herzog conversation, full of stories that sound like tall tales if it weren't for the fact that they come from the life of Werner Herzog and must therefore be true. In fact, he had travelled all the way from Guyana, where he was shooting an airship floating above the canopy of a rainforest (for his documentary The White Diamond), just because Ebert had asked if he could come show Invincible. Herzog is a loyal friend; he returned again this year. I met him briefly, asking him to sign my box set, and he kept repeating, "Vere is Roger? Vere is Roger?"

Gates of Heaven/Invincible (1980/2001, at Ebertfest in 2004). Errol Morris was presenting his modest 1980 documentary about a pet cemetery, which Ebert has long declared one of the best films ever made, and with him was Werner Herzog, director of Invincible, which was scheduled for a screening later that day. Back in the late 70's, Morris had told his friend Herzog he was going to make a movie, and Herzog replied that if Morris ever made a movie, he'd eat his shoe. Sure enough, Gates of Heaven was inexplicably produced, and Herzog appeared in a short film shot by Les Blank entitled "Werner Herzog Eats His Shoe." It was exactly what it claimed to be. After Gates of Heaven screened, a giddy Morris--who had just won his first Oscar, for Fog of War--sparred with the audience during a Q&A, answering questions with either glib jokes or stunning anecdotes. I still remember what he said regarding his interview technique, and have quoted it often: "If you let anyone talk long enough, eventually they will prove themselves to be completely crazy." There was a film screened between Gates of Heaven and Invincible, but it wasn't very good, so let's skip straight to the Herzog. Invincible is good, and definitely overlooked, but what sticks with me most is his extended Q&A afterward. It was getting very late, so most of the theater left, but those who stayed were treated to a typically astounding Herzog conversation, full of stories that sound like tall tales if it weren't for the fact that they come from the life of Werner Herzog and must therefore be true. In fact, he had travelled all the way from Guyana, where he was shooting an airship floating above the canopy of a rainforest (for his documentary The White Diamond), just because Ebert had asked if he could come show Invincible. Herzog is a loyal friend; he returned again this year. I met him briefly, asking him to sign my box set, and he kept repeating, "Vere is Roger? Vere is Roger?" A Hard Day's Night (1964, then 2004). The Beatles can always provide a transcendent theater experience, although it's only to their favor that no one's going to be playing Magical Mystery Tour theatrically anytime soon. Roger Ebert came up to the Wisconsin Film Festival to introduce this screening, one of his "Great Movies," but what really sticks out in my memory is this little boy who was sitting next to me, bopping his head along with the songs. When John Lennon was sitting in the bathtub, playing WWII games with his toy boats, the boy pulled at his mother's sleeve and said, "I love this part!" That kind of made the movie for me. Later that night we saw the 70's schlock film Giant Spider Invasion hosted by Kevin Murphy from Mystery Science Theater 3000, and that could easily be included on this list too.

A Hard Day's Night (1964, then 2004). The Beatles can always provide a transcendent theater experience, although it's only to their favor that no one's going to be playing Magical Mystery Tour theatrically anytime soon. Roger Ebert came up to the Wisconsin Film Festival to introduce this screening, one of his "Great Movies," but what really sticks out in my memory is this little boy who was sitting next to me, bopping his head along with the songs. When John Lennon was sitting in the bathtub, playing WWII games with his toy boats, the boy pulled at his mother's sleeve and said, "I love this part!" That kind of made the movie for me. Later that night we saw the 70's schlock film Giant Spider Invasion hosted by Kevin Murphy from Mystery Science Theater 3000, and that could easily be included on this list too. Au Hasard Balthazar (2005). At a party I told an Italian research scientist, Giulio, that I really wanted to see Au Hasard Balthazar, that "film about a donkey," which at the time was unavailable on DVD. He sighed, put his hands to his heart, and said, "Oh, it's beautiful!" So imagine how thrilled I was that it was scheduled for the Wisconsin Film Festival in 2005. The night before the screening, I was standing in line with a French woman who was amused that I disliked Godard's latest film. I told her we were seeing Au Hasard Balthazar the next day: she put her hands to her heart and said, "Oh, what a beautiful film!" Now imagine my condition. After the film had ended, I did find it beautiful, but it was so deeply sad and moving--exquisitely so, but still--that I was crying for days after that. Now when I watch it on DVD, it's like a sacred experience.

Au Hasard Balthazar (2005). At a party I told an Italian research scientist, Giulio, that I really wanted to see Au Hasard Balthazar, that "film about a donkey," which at the time was unavailable on DVD. He sighed, put his hands to his heart, and said, "Oh, it's beautiful!" So imagine how thrilled I was that it was scheduled for the Wisconsin Film Festival in 2005. The night before the screening, I was standing in line with a French woman who was amused that I disliked Godard's latest film. I told her we were seeing Au Hasard Balthazar the next day: she put her hands to her heart and said, "Oh, what a beautiful film!" Now imagine my condition. After the film had ended, I did find it beautiful, but it was so deeply sad and moving--exquisitely so, but still--that I was crying for days after that. Now when I watch it on DVD, it's like a sacred experience. The Holy Mountain/Santa Sangre (1973/1989, later 2005). Alejandro Jodorowsky, director of the cult film El Topo, lives in France, where he writes comic books and novels, gives tarot card readings, and teaches classes in "psychomagic," which is very similar to psychotherapy. He's a difficult guy to meet if you live in Wisconsin, so when I heard that he would be at a horror/SF/anime expo in Toronto for a signing and a screening, I embarked upon a pilgrimage. I was second in an unfortunately short line (for his films had been unavailable in America for decades), but was enthusiastically greeted by actor Robert John Skipper (the gunfighter's son in El Topo), who signed my El Topo soundtrack, and then Jodorowsky himself, who had lit incense at the table and met every fan with a Cheshire Cat smile. He struggled with English, so he only understood my praise for one of his short stories when he interpreted my hand gestures: "I love the story about the boy who cries tears of gold," I said, and moved my fingers down my face. He lit up. "Ah, yes, Ladronn! [A comic book artist.] I love that one! That came out here?" Later that night, he hosted a double feature of his films The Holy Mountain and Santa Sangre. The former was to be a rare print, but was so prized that it was stolen in transit. We had to watch a Japanese DVD instead, which was censored, with white blobs obscuring exposed genitals. "I kind of like this," Jodorowsky said after the film. "They are like halos around the sex." He seemed a bit embarrassed by The Holy Mountain, as he's since moved past its obscure symbolism (although it's still a favorite of mine); he was more excited about showing Santa Sangre in a pristine print. It was a crazy night, full of bizarre Jodorowsky anecdotes, but it was also elating, because he announced that he had finally reconciled with longtime nemesis Allen Klein, owner of the North American rights to El Topo and The Holy Mountain. "We faced one other and saw our white beards, and we saw we were both old men. We embraced!" Those films are finally being released on DVD this week.

The Holy Mountain/Santa Sangre (1973/1989, later 2005). Alejandro Jodorowsky, director of the cult film El Topo, lives in France, where he writes comic books and novels, gives tarot card readings, and teaches classes in "psychomagic," which is very similar to psychotherapy. He's a difficult guy to meet if you live in Wisconsin, so when I heard that he would be at a horror/SF/anime expo in Toronto for a signing and a screening, I embarked upon a pilgrimage. I was second in an unfortunately short line (for his films had been unavailable in America for decades), but was enthusiastically greeted by actor Robert John Skipper (the gunfighter's son in El Topo), who signed my El Topo soundtrack, and then Jodorowsky himself, who had lit incense at the table and met every fan with a Cheshire Cat smile. He struggled with English, so he only understood my praise for one of his short stories when he interpreted my hand gestures: "I love the story about the boy who cries tears of gold," I said, and moved my fingers down my face. He lit up. "Ah, yes, Ladronn! [A comic book artist.] I love that one! That came out here?" Later that night, he hosted a double feature of his films The Holy Mountain and Santa Sangre. The former was to be a rare print, but was so prized that it was stolen in transit. We had to watch a Japanese DVD instead, which was censored, with white blobs obscuring exposed genitals. "I kind of like this," Jodorowsky said after the film. "They are like halos around the sex." He seemed a bit embarrassed by The Holy Mountain, as he's since moved past its obscure symbolism (although it's still a favorite of mine); he was more excited about showing Santa Sangre in a pristine print. It was a crazy night, full of bizarre Jodorowsky anecdotes, but it was also elating, because he announced that he had finally reconciled with longtime nemesis Allen Klein, owner of the North American rights to El Topo and The Holy Mountain. "We faced one other and saw our white beards, and we saw we were both old men. We embraced!" Those films are finally being released on DVD this week. The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King (2005). Nothing special about the screening itself, but the audience made this one unique. I didn't recall any particular cultishness in the crowd of the first Lord of the Rings film, The Fellowship of the Ring--few were Peter Jackson fans, and though there were plenty of Tolkien fans, presumably, none dressed up or seemed to express any slavish desire to this particular adaptation. By the third film (and already by the second), attending a screening was like attending a convention. Everyone was giddy and excited and part of the same circuit of energy that was flowing from the screen. Not a person in the house wasn't a fan. As the ending credits began to scroll, I think we all felt a little bittersweet. It was over--no more Lord of the Rings films. A major cinematic event had ended. You can complain that the film had too many endings (as I sometimes do), but man, there were people in that theater that were bawling when those hobbits hugged each other farewell.

The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King (2005). Nothing special about the screening itself, but the audience made this one unique. I didn't recall any particular cultishness in the crowd of the first Lord of the Rings film, The Fellowship of the Ring--few were Peter Jackson fans, and though there were plenty of Tolkien fans, presumably, none dressed up or seemed to express any slavish desire to this particular adaptation. By the third film (and already by the second), attending a screening was like attending a convention. Everyone was giddy and excited and part of the same circuit of energy that was flowing from the screen. Not a person in the house wasn't a fan. As the ending credits began to scroll, I think we all felt a little bittersweet. It was over--no more Lord of the Rings films. A major cinematic event had ended. You can complain that the film had too many endings (as I sometimes do), but man, there were people in that theater that were bawling when those hobbits hugged each other farewell. Faust w/the short "Daddy, Don't!" (1926/2006). F.W. Murnau's Faust is one of the greatest of all silent films, and was the perfect capper to the UW Cinematheque's 2006 Murnau retrospective. David Drazin, a musician from Chicago, would drive the three hours up to Madison every Friday night--even through snowstorms--to provide live piano accompaniment to each of the films, and he was at his best creating a thunderous crescendo in a scene where Faust is lifted and carried high over the countryside by the Devil. Before the film, a short was screened by a UW student, "Daddy, Don't!" The silent film pastiche depicts a father who, when he drinks from a giant jug marked XXX, becomes violent toward his wife and son. At one point Drazin, fed up with the activity on-screen, stops playing, stands, and storms out of the theater, only to emerge on the screen and seize the bottle from the alcoholic husband. Cheers from the audience. Another reason I love the Cinematheque.

Faust w/the short "Daddy, Don't!" (1926/2006). F.W. Murnau's Faust is one of the greatest of all silent films, and was the perfect capper to the UW Cinematheque's 2006 Murnau retrospective. David Drazin, a musician from Chicago, would drive the three hours up to Madison every Friday night--even through snowstorms--to provide live piano accompaniment to each of the films, and he was at his best creating a thunderous crescendo in a scene where Faust is lifted and carried high over the countryside by the Devil. Before the film, a short was screened by a UW student, "Daddy, Don't!" The silent film pastiche depicts a father who, when he drinks from a giant jug marked XXX, becomes violent toward his wife and son. At one point Drazin, fed up with the activity on-screen, stops playing, stands, and storms out of the theater, only to emerge on the screen and seize the bottle from the alcoholic husband. Cheers from the audience. Another reason I love the Cinematheque. Satantango (1994/2006). Sitting through eight hours of Bela Tarr's Satantango promised at the outset to be a chore, but a sizeable crowd appeared that Saturday morning like stoic marathon runners prepared for the challenge. Nine hours later (allowing for a 1-hour dinner break), those who'd survived the journey were elated, transformed. Even the world had metamorphosed, as we stepped out on streets marked by the first snow of the winter.

Satantango (1994/2006). Sitting through eight hours of Bela Tarr's Satantango promised at the outset to be a chore, but a sizeable crowd appeared that Saturday morning like stoic marathon runners prepared for the challenge. Nine hours later (allowing for a 1-hour dinner break), those who'd survived the journey were elated, transformed. Even the world had metamorphosed, as we stepped out on streets marked by the first snow of the winter.The power of cinema!

Hiç yorum yok:

Yorum Gönder