I first encountered the 1970 Mexican film El Topo the same way a lot of people did who were too young to catch the film in its theater run; I encountered it in the library, or publicity stills of it anyway, as excerpted in the book Midnight Movies. This black-and-white cult film survey called El Topo the "first midnight movie," and so now we all say that it was, besting Rocky Horror by a few years. The images from that book stick in my mind so strongly that when I watch El Topo now, I still find myself disconcerted to see them moving. And with what life and energy! The legless man perched on the back of the armless man, staring forward resolutely as a single unit...the diapered tyrant writhing on the floor in his beehive-shaped fort...the nude hippy girl with the boyish physique holding a black umbrella while she wades in a desert oasis...and that umbrella hanging over the head of the black-clad master gunfighter, who rides on a horse through the desert with his naked son, leaving behind a framed picture of the boy's mother, half-buried in the sand. This last image has become so famous that it's now as synonymous with surrealist cinema as Dali and Bunuel slitting open an eye. Chilean-born director Alejandro Jodorowsky was not a Surrealist, capital "S"--that movement lasted for barely a heartbeat before its originators began to disown the label for all its limitations--but certainly he is a master of creating images that are spectacular, arresting, or mesmerizing simply because they exist, because he somehow managed to corral the resources to produce them. Perhaps for this very reason, he has not made very many films, and in recent decades has turned his attention to comic books, where he can let his imagination go unfettered, free of movie producers, special effects budgets, reserve and reason.

I first encountered the 1970 Mexican film El Topo the same way a lot of people did who were too young to catch the film in its theater run; I encountered it in the library, or publicity stills of it anyway, as excerpted in the book Midnight Movies. This black-and-white cult film survey called El Topo the "first midnight movie," and so now we all say that it was, besting Rocky Horror by a few years. The images from that book stick in my mind so strongly that when I watch El Topo now, I still find myself disconcerted to see them moving. And with what life and energy! The legless man perched on the back of the armless man, staring forward resolutely as a single unit...the diapered tyrant writhing on the floor in his beehive-shaped fort...the nude hippy girl with the boyish physique holding a black umbrella while she wades in a desert oasis...and that umbrella hanging over the head of the black-clad master gunfighter, who rides on a horse through the desert with his naked son, leaving behind a framed picture of the boy's mother, half-buried in the sand. This last image has become so famous that it's now as synonymous with surrealist cinema as Dali and Bunuel slitting open an eye. Chilean-born director Alejandro Jodorowsky was not a Surrealist, capital "S"--that movement lasted for barely a heartbeat before its originators began to disown the label for all its limitations--but certainly he is a master of creating images that are spectacular, arresting, or mesmerizing simply because they exist, because he somehow managed to corral the resources to produce them. Perhaps for this very reason, he has not made very many films, and in recent decades has turned his attention to comic books, where he can let his imagination go unfettered, free of movie producers, special effects budgets, reserve and reason. As I've mentioned in this blog before, when I was living in Seattle in 1998-2000 I serendipitously found myself in an apartment within a few blocks of the greatest video store on the planet, Scarecrow Video. The jewel in their near-comprehensive collection of cinema--at the time, anyway--were two imported Japanese VHS tapes, one of El Topo, the other of Jodorowsky's follow-up, The Holy Mountain (1973). The film was, in many ways, exactly what I expected, but that's something remarkable, because in the intervening years between first seeing those simple black-and-white stills in the Midnight Movies book and watching this tape, my imagination had naturally run rampant. When I saw those pictures I was both repelled and fascinated, and the film had the same effect. But best of all, it was intent on transporting me to another world, a purely allegorical landscape and a realm of extreme violence and ritualistic magic. It's a dream-realm, visited successfully by only a few directors; and in this case one can imagine the characters of Jean Cocteau and Luis Bunuel (Simon of the Desert in particular) inhabit it. Base impulses--lust, hatred, and jealousy--are intense enough, in the deserts of El Topo and the climes of The Holy Mountain, to actually shape the landscape and summon shamans and demons. His are films of magical realism, but he has lived in enough countries, and speaks enough languages, that they are also confoundingly international films. El Topo's horrendous English-dubbed soundtrack has, in the decades before this final, official release in its original language this spring, been so widely experienced that it has almost supplanted itself as the official version. The Holy Mountain was shot in English, but sounds just as dubbed, and convinced me before its new release on DVD that it was another completely Mexican production. As Jodorowsky explains on the newly-recorded audio commentary, Holy Mountain had no country, which spoiled its chances of a prize from Cannes. But anyone who tries to categorize the films of Jodorowsky will find themselves frustrated.

As I've mentioned in this blog before, when I was living in Seattle in 1998-2000 I serendipitously found myself in an apartment within a few blocks of the greatest video store on the planet, Scarecrow Video. The jewel in their near-comprehensive collection of cinema--at the time, anyway--were two imported Japanese VHS tapes, one of El Topo, the other of Jodorowsky's follow-up, The Holy Mountain (1973). The film was, in many ways, exactly what I expected, but that's something remarkable, because in the intervening years between first seeing those simple black-and-white stills in the Midnight Movies book and watching this tape, my imagination had naturally run rampant. When I saw those pictures I was both repelled and fascinated, and the film had the same effect. But best of all, it was intent on transporting me to another world, a purely allegorical landscape and a realm of extreme violence and ritualistic magic. It's a dream-realm, visited successfully by only a few directors; and in this case one can imagine the characters of Jean Cocteau and Luis Bunuel (Simon of the Desert in particular) inhabit it. Base impulses--lust, hatred, and jealousy--are intense enough, in the deserts of El Topo and the climes of The Holy Mountain, to actually shape the landscape and summon shamans and demons. His are films of magical realism, but he has lived in enough countries, and speaks enough languages, that they are also confoundingly international films. El Topo's horrendous English-dubbed soundtrack has, in the decades before this final, official release in its original language this spring, been so widely experienced that it has almost supplanted itself as the official version. The Holy Mountain was shot in English, but sounds just as dubbed, and convinced me before its new release on DVD that it was another completely Mexican production. As Jodorowsky explains on the newly-recorded audio commentary, Holy Mountain had no country, which spoiled its chances of a prize from Cannes. But anyone who tries to categorize the films of Jodorowsky will find themselves frustrated.El Topo, for example, may seem like a spaghetti Western at first glance, as its merciless, Eastwood-like gunfighter, soullessly clad in black despite the fact that he rides through a bleak desert, duels with some bandits, breaks up a gang, and liberates a monastery. But it quickly takes on the sublime poetics of a Zen folktale. The woman he frees from a despot in the desert tells him about four mystic Masters with whom he must duel and defeat to prove his supremacy. Each unique Master he swiftly hunts down--one is impervious to bullets; one has a lion and a wife who caws like a bird; one is surrounded by a pen of rabbits; one can deflect bullets with a net. He defeats each one, only to be betrayed by the woman who brought him here and the mysterious, black-clad succubus who accompanies them. He's killed and resurrected--deep in a mountain, tended by exiled victims of disease and deformity who hope that he will be the one who leads them to the light (he is a mole, "el topo," who, though blind, digs tenaciously toward the surface). In this, the second half of the story, the gunfighter journeys to a corrupt city and becomes a beggar, accompanied by the woman who loves him, a dwarf from the mountains. Together they struggle to liberate their subterranean colony while being mistreated by the vain and cruel townspeople.

El Topo made Jodorowsky's reputation, not least because he's credited as director, writer, actor (he plays the lead), and music composer (the soundtrack was released on the Beatles' Apple Records). Those who saw the film envisioned him to be a Zen superman, a pillar of wisdom, and they watched the film religiously, picking apart the arcane symbols as though it were a psychedelic Bible. But Jodorowsky was already middle-aged, having spent years in Europe writing mime performances for friend Marcel Marceau and directing plays as part of the Panic Movement, a confrontational street theater, founded with Fernando Arrabal (Viva La Muerte) and Roland Topor (the cartoonist and author), designed to shock the audience out of stupor. He was an unlikely Messiah, but he took the role seriously, giving interviews in which he proudly proclaimed that the miraculous rocks from which El Topo's women drink were piled to form a perfect replica of his phallus...etc., etc. He made it easier for critics to dismiss him as pretentious, but to dismiss El Topo is to overlook those virtues which make it so valuable.

It might take a few viewings to see the merits of any of Jodorowsky's films, but the merits do float to the surface once the film settles in your consciousness. On the other hand, you need only see El Topo once--say, ideally, in 1970 during its original midnight-movie run in New York, when Everyone who was Anyone had to attend--and the film's images will so stain your retinas that they'll follow you for the rest of your life, for better or worse. He's an original, but more than that, he almost seems to be tapped into the Jungian collective unconscious. It doesn't matter that his films are flawed (and they are). They still fire parts of your brain which are usually dormant during your waking hours, and that can't be underestimated. So yes, El Topo is often hippy-dippy naive (and chauvenist--a trait which fades in his later works). But it contains enough savagery and cynicism to compensate for that. He's an artist working straight from his dreams. He's subverting his own critical faculties to bring you these images and ideas, his stream-of-consciousness steered only by an innate storytelling skill.

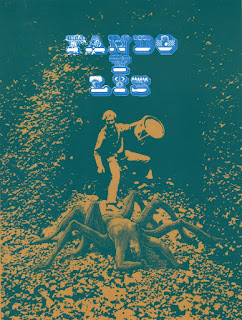

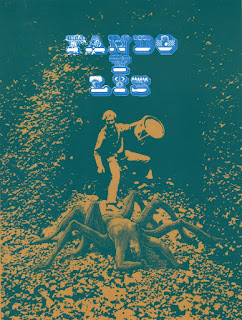

The storytelling is much more distinct in El Topo than in his preceding film, Fando y Lis, but that may have much to do with the fact that he's adapting another's material. Fando y Lis is a play by Arrabal, and Jodorowsky directed it, he says, without a script and from memory, though one can imagine that the result is something with which Arrabal was pleased. (I watched the riddle-like interview with Arrabal on the Viva La Muerte DVD, and I really couldn't tell.) Enacted in some kind of post-apocalyptic wasteland akin to the one in El Topo--with jagged rocks and forbidding, shadowy hills replacing El Topo's vast desert--it's an avant-garde film in the Panic mold, a film to enrage rather than to be enjoyed. Since most of the modern-day, film-savvy viewers will not be enraged, it acts more as a curiosity piece, a stunt in the mold of John Waters which has an ending more haunting and moving than it really ought to be--a testament to Jodorowsky's budding skill as a filmmaker. The "story" follows childish lovers Fando--Arrabal's surrogate--and Lis, who is paralyzed and pulled by Fando in a wagon as they journey toward the mythical city of Tar, a paradise which probably doesn't exist. Along the way they meet various corrupt temptations, Pilgrim's Progress-style, including a pack of transvestites and some lecherous old men. It should have been a short film, but it does attain a certain power by its conclusion, however inevitable and predictible the actual results are. Supposedly the film caused a riot at the Acapulco Film Festival where it premiered in 1968, and Jodorowsky barely escaped from the screening alive. Well, it was that kind of year.

The storytelling is much more distinct in El Topo than in his preceding film, Fando y Lis, but that may have much to do with the fact that he's adapting another's material. Fando y Lis is a play by Arrabal, and Jodorowsky directed it, he says, without a script and from memory, though one can imagine that the result is something with which Arrabal was pleased. (I watched the riddle-like interview with Arrabal on the Viva La Muerte DVD, and I really couldn't tell.) Enacted in some kind of post-apocalyptic wasteland akin to the one in El Topo--with jagged rocks and forbidding, shadowy hills replacing El Topo's vast desert--it's an avant-garde film in the Panic mold, a film to enrage rather than to be enjoyed. Since most of the modern-day, film-savvy viewers will not be enraged, it acts more as a curiosity piece, a stunt in the mold of John Waters which has an ending more haunting and moving than it really ought to be--a testament to Jodorowsky's budding skill as a filmmaker. The "story" follows childish lovers Fando--Arrabal's surrogate--and Lis, who is paralyzed and pulled by Fando in a wagon as they journey toward the mythical city of Tar, a paradise which probably doesn't exist. Along the way they meet various corrupt temptations, Pilgrim's Progress-style, including a pack of transvestites and some lecherous old men. It should have been a short film, but it does attain a certain power by its conclusion, however inevitable and predictible the actual results are. Supposedly the film caused a riot at the Acapulco Film Festival where it premiered in 1968, and Jodorowsky barely escaped from the screening alive. Well, it was that kind of year.

El Topo expands upon the themes of Fando y Lis but Jodorowsky also refines his skill and heightens the art. His third film, The Holy Mountain, was considered a flop upon its release, but only because nobody really had a chance to see it. With the new DVD box set The Films of Alejandro Jodorowsky finally bringing his filmography to a wider audience, it seems that Holy Mountain's reputation is being restored to the point where many critics are now discussing it as the superior film. To be sure, it's the wildest, and the most pure expression of his imagination on film (and thus, even closer to his comics). While it once again blurs genres, it is ostensibly a science fiction piece, set in a world (perhaps the near future) of mass poverty and prostitution and ruled by a corrupt and hypocritical papacy. The symbols and coded imagery come fast and furious from the onset of the film. Here, for example, is the opening: during the credits, we see a black-clad Master (Jodorowsky again), wearing a wide-brimmed hat and a cloak, who is kneeling between two blonde female disciples in some kind of sacred chamber. He strips the women, removes their false fingernails, shaves their heads and pushes them together so that all three form the shape of a mountain: essentially they are foreshadowing the procession of events in the story, as we will see our characters rid themselves of material possessions, achieve a spiritual nakedness, and ascend the mountain to find their transcendence. But then the images come more quickly: models of the cosmos and unblinking eyes, one door opening with another revealing a key, mummified bodies, God knows what else. We see a thief lying in his own urine in the dirt, his face covered in flies. A tarot card lying nearby identifies him as the Fool. A cougar beside him roars. We see another tarot card strapped to the back of a legless and armless man who energetically hobbles through the street toward the Fool, and so on, almost unrelentingly for two full hours! But the narrative is pretty straightforward: this Fool, identified in the film as the Thief, climbs a Tower (like the tower of the Tarot), and within it encounters Jodorowsky's Zen master, who teaches him that he needn't seek gold, because we all have gold within us (he demonstrates this by alchemically converting the man's sweat, urine, and feces into an unattractive lump of gold). Then he--and the tattooed woman who accompanies him--lead the Thief into a chamber with the effigies of various men and women from different planets. Each tells of his world, and it's here, just as the narrative is getting bogged down, that the film takes off, with brilliant bits of satire, astonishing set design, and gleefully Bunuellian blasphemy. Finally, when our cast is introduced, all of the "thieves"--nine for the nine planets--join a mission to climb a holy mountain, at the zenith of which they will find some kind of ultimate meaning or transcendent insight. But even this becomes not quite what we expect, as Jodorowsky breaks the fourth wall, directly addresses the viewer, and demonstrates that all earthly pursuits are "maya," illusion. The imagery in Holy Mountain can be the stuff of nightmares, but only in one scene is it actually intended to be--when each of the pilgrims face their darkest fear. For the rest of the film, the extreme images are strangely defused by Jodorowsky's matter-of-fact handling of the material. Corpses mechanized to provide sex shows, a giant phallic ice sculpture assaulted at a banquet by lustful upperclass women, a room full of severed testicles preserved in jars--Jodorowsky observes these peculiar sights like a bemused documentarian. In this way, not much seems "shocking." Blood, bodies, sex, and mud are all part of the same continuum. His excitement for his own ideas translates to the screen, and his best scenes pick up on this electric energy with a pulsating rhythm to the editing: the aforementioned scene of the legless man hobbling quickly through the street; a reenactment of Spain's conquering of Mexico with frogs meticulously disguised as Aztecs and iguanas playing conquistadors; a montage of religious-themed weaponry set to a guitar-rock soundtrack; the demonstration of an immense robot vagina which must be stimulated by penetrating it with a giant, awkwardly-wielded rod--which ends with a perfectly edited gag.

El Topo expands upon the themes of Fando y Lis but Jodorowsky also refines his skill and heightens the art. His third film, The Holy Mountain, was considered a flop upon its release, but only because nobody really had a chance to see it. With the new DVD box set The Films of Alejandro Jodorowsky finally bringing his filmography to a wider audience, it seems that Holy Mountain's reputation is being restored to the point where many critics are now discussing it as the superior film. To be sure, it's the wildest, and the most pure expression of his imagination on film (and thus, even closer to his comics). While it once again blurs genres, it is ostensibly a science fiction piece, set in a world (perhaps the near future) of mass poverty and prostitution and ruled by a corrupt and hypocritical papacy. The symbols and coded imagery come fast and furious from the onset of the film. Here, for example, is the opening: during the credits, we see a black-clad Master (Jodorowsky again), wearing a wide-brimmed hat and a cloak, who is kneeling between two blonde female disciples in some kind of sacred chamber. He strips the women, removes their false fingernails, shaves their heads and pushes them together so that all three form the shape of a mountain: essentially they are foreshadowing the procession of events in the story, as we will see our characters rid themselves of material possessions, achieve a spiritual nakedness, and ascend the mountain to find their transcendence. But then the images come more quickly: models of the cosmos and unblinking eyes, one door opening with another revealing a key, mummified bodies, God knows what else. We see a thief lying in his own urine in the dirt, his face covered in flies. A tarot card lying nearby identifies him as the Fool. A cougar beside him roars. We see another tarot card strapped to the back of a legless and armless man who energetically hobbles through the street toward the Fool, and so on, almost unrelentingly for two full hours! But the narrative is pretty straightforward: this Fool, identified in the film as the Thief, climbs a Tower (like the tower of the Tarot), and within it encounters Jodorowsky's Zen master, who teaches him that he needn't seek gold, because we all have gold within us (he demonstrates this by alchemically converting the man's sweat, urine, and feces into an unattractive lump of gold). Then he--and the tattooed woman who accompanies him--lead the Thief into a chamber with the effigies of various men and women from different planets. Each tells of his world, and it's here, just as the narrative is getting bogged down, that the film takes off, with brilliant bits of satire, astonishing set design, and gleefully Bunuellian blasphemy. Finally, when our cast is introduced, all of the "thieves"--nine for the nine planets--join a mission to climb a holy mountain, at the zenith of which they will find some kind of ultimate meaning or transcendent insight. But even this becomes not quite what we expect, as Jodorowsky breaks the fourth wall, directly addresses the viewer, and demonstrates that all earthly pursuits are "maya," illusion. The imagery in Holy Mountain can be the stuff of nightmares, but only in one scene is it actually intended to be--when each of the pilgrims face their darkest fear. For the rest of the film, the extreme images are strangely defused by Jodorowsky's matter-of-fact handling of the material. Corpses mechanized to provide sex shows, a giant phallic ice sculpture assaulted at a banquet by lustful upperclass women, a room full of severed testicles preserved in jars--Jodorowsky observes these peculiar sights like a bemused documentarian. In this way, not much seems "shocking." Blood, bodies, sex, and mud are all part of the same continuum. His excitement for his own ideas translates to the screen, and his best scenes pick up on this electric energy with a pulsating rhythm to the editing: the aforementioned scene of the legless man hobbling quickly through the street; a reenactment of Spain's conquering of Mexico with frogs meticulously disguised as Aztecs and iguanas playing conquistadors; a montage of religious-themed weaponry set to a guitar-rock soundtrack; the demonstration of an immense robot vagina which must be stimulated by penetrating it with a giant, awkwardly-wielded rod--which ends with a perfectly edited gag.

Another moment is in Santa Sangre (1989), Jodorowsky's return to filmmaking after a long absence: a sudden cut to a bird sailing over a city while throbbing salsa music plays; or, even better, a group with Down's syndrome being led by a drug dealer in a dance down a street of prostitutes--the closest, perhaps, that Jodorowsky has ever come to filming a musical. When I saw him introducing a double-feature of Holy Mountain and Santa Sangre in Toronto a few years ago, he seemed embarrassed by the exhausting symbology of the former, and introduced Santa Sangre as his personal favorite. Truly, it represents an evolution in his storytelling, which you can chart more gradually by reading his French comics and (I assume) novels and essays. If El Topo riffed on the Western genre, and Holy Mountain on science fiction, Santa Sangre is Jodorowsky's take on horror; it's produced by Claudio Argento, who likely insisted upon a lot of gore and creative murders, but it reveals itself slowly as an extension of the director's psychology-driven philosophies. Fenix (Axel Jodorowsky, one of the director's sons), imprisoned in a mental institution, recalls his past: the little mute girl he loved; his father, who scarred his chest in the shape of an eagle as a rite of passage; the traumatic moment when he witnessed his mother's arms being cut from her body by her sadistic, philandering husband. He now serves his mother, worships her, even acts as her arms so that she can play the piano again and preen before a mirror; but he has lost his own identity in the process, and is driven to murder by her jealous whims. It's a little bit like Hitchcock's Psycho (as Jodorowsky proudly admits), but the whole mix is something you've never seen before, as original as the elephant funeral scene which occurs early in the film, and about which Roger Ebert has written so eloquently. (Ebert is one of the film's most vocal admirers.) If Holy Mountain was, as Jodorowsky explains on his commentary track, a film made to change the world, Santa Sangre is a film made to change the individual--a plea to free oneself from the grip of one's parents and to forge a new identity.

Another moment is in Santa Sangre (1989), Jodorowsky's return to filmmaking after a long absence: a sudden cut to a bird sailing over a city while throbbing salsa music plays; or, even better, a group with Down's syndrome being led by a drug dealer in a dance down a street of prostitutes--the closest, perhaps, that Jodorowsky has ever come to filming a musical. When I saw him introducing a double-feature of Holy Mountain and Santa Sangre in Toronto a few years ago, he seemed embarrassed by the exhausting symbology of the former, and introduced Santa Sangre as his personal favorite. Truly, it represents an evolution in his storytelling, which you can chart more gradually by reading his French comics and (I assume) novels and essays. If El Topo riffed on the Western genre, and Holy Mountain on science fiction, Santa Sangre is Jodorowsky's take on horror; it's produced by Claudio Argento, who likely insisted upon a lot of gore and creative murders, but it reveals itself slowly as an extension of the director's psychology-driven philosophies. Fenix (Axel Jodorowsky, one of the director's sons), imprisoned in a mental institution, recalls his past: the little mute girl he loved; his father, who scarred his chest in the shape of an eagle as a rite of passage; the traumatic moment when he witnessed his mother's arms being cut from her body by her sadistic, philandering husband. He now serves his mother, worships her, even acts as her arms so that she can play the piano again and preen before a mirror; but he has lost his own identity in the process, and is driven to murder by her jealous whims. It's a little bit like Hitchcock's Psycho (as Jodorowsky proudly admits), but the whole mix is something you've never seen before, as original as the elephant funeral scene which occurs early in the film, and about which Roger Ebert has written so eloquently. (Ebert is one of the film's most vocal admirers.) If Holy Mountain was, as Jodorowsky explains on his commentary track, a film made to change the world, Santa Sangre is a film made to change the individual--a plea to free oneself from the grip of one's parents and to forge a new identity.

He made two other films--Tusk (1980), a film that's almost impossible to see now, and The Rainbow Thief (1990), which Jodorowsky filmed as a favor for a friend--but he has disowned both. I'll withhold judgment until I've seen them. But I maintain that the best work Jodorowsky has done is not on film but in the medium of comics. After an aborted attempt in the late 70's to film an adaptation of Frank Herbert's Dune, Jodorowsky decided instead to create a science fiction comic book with one of that film's art designers, Jean Giraud, aka Moebius (creator of the Western comic book Blueberry). Moebius is generally considered one of the greatest living illustrators in comics, and The Incal is regarded--particularly in Europe, where it is better known--as a masterpiece of the form. Once again influenced by the Tarot (Jodorowsky has the largest Tarot collection in the world, and is considered an authority on the subject), the four-part epic is built around four consecutive movements--up, down, left, and right--as its bizarre, semi-comical cast, led by John DiFool (an everyman standing in for the "Fool" of the Tarot), explore a vertical metropolis built into a chasm in a planet and ruled by a tyrannical hermaphrodite and his/her "technopriests"--and then journey to the edges of the cosmos. Unlike most of Jodorowsky's comic book work, this has been intermittently made available in English, first in four lavish volumes published by the Marvel imprint Epic, and more recently from the (sadly, now-defunct) Humanoids Publishing.

He made two other films--Tusk (1980), a film that's almost impossible to see now, and The Rainbow Thief (1990), which Jodorowsky filmed as a favor for a friend--but he has disowned both. I'll withhold judgment until I've seen them. But I maintain that the best work Jodorowsky has done is not on film but in the medium of comics. After an aborted attempt in the late 70's to film an adaptation of Frank Herbert's Dune, Jodorowsky decided instead to create a science fiction comic book with one of that film's art designers, Jean Giraud, aka Moebius (creator of the Western comic book Blueberry). Moebius is generally considered one of the greatest living illustrators in comics, and The Incal is regarded--particularly in Europe, where it is better known--as a masterpiece of the form. Once again influenced by the Tarot (Jodorowsky has the largest Tarot collection in the world, and is considered an authority on the subject), the four-part epic is built around four consecutive movements--up, down, left, and right--as its bizarre, semi-comical cast, led by John DiFool (an everyman standing in for the "Fool" of the Tarot), explore a vertical metropolis built into a chasm in a planet and ruled by a tyrannical hermaphrodite and his/her "technopriests"--and then journey to the edges of the cosmos. Unlike most of Jodorowsky's comic book work, this has been intermittently made available in English, first in four lavish volumes published by the Marvel imprint Epic, and more recently from the (sadly, now-defunct) Humanoids Publishing.

El Topo made Jodorowsky's reputation, not least because he's credited as director, writer, actor (he plays the lead), and music composer (the soundtrack was released on the Beatles' Apple Records). Those who saw the film envisioned him to be a Zen superman, a pillar of wisdom, and they watched the film religiously, picking apart the arcane symbols as though it were a psychedelic Bible. But Jodorowsky was already middle-aged, having spent years in Europe writing mime performances for friend Marcel Marceau and directing plays as part of the Panic Movement, a confrontational street theater, founded with Fernando Arrabal (Viva La Muerte) and Roland Topor (the cartoonist and author), designed to shock the audience out of stupor. He was an unlikely Messiah, but he took the role seriously, giving interviews in which he proudly proclaimed that the miraculous rocks from which El Topo's women drink were piled to form a perfect replica of his phallus...etc., etc. He made it easier for critics to dismiss him as pretentious, but to dismiss El Topo is to overlook those virtues which make it so valuable.

It might take a few viewings to see the merits of any of Jodorowsky's films, but the merits do float to the surface once the film settles in your consciousness. On the other hand, you need only see El Topo once--say, ideally, in 1970 during its original midnight-movie run in New York, when Everyone who was Anyone had to attend--and the film's images will so stain your retinas that they'll follow you for the rest of your life, for better or worse. He's an original, but more than that, he almost seems to be tapped into the Jungian collective unconscious. It doesn't matter that his films are flawed (and they are). They still fire parts of your brain which are usually dormant during your waking hours, and that can't be underestimated. So yes, El Topo is often hippy-dippy naive (and chauvenist--a trait which fades in his later works). But it contains enough savagery and cynicism to compensate for that. He's an artist working straight from his dreams. He's subverting his own critical faculties to bring you these images and ideas, his stream-of-consciousness steered only by an innate storytelling skill.

The storytelling is much more distinct in El Topo than in his preceding film, Fando y Lis, but that may have much to do with the fact that he's adapting another's material. Fando y Lis is a play by Arrabal, and Jodorowsky directed it, he says, without a script and from memory, though one can imagine that the result is something with which Arrabal was pleased. (I watched the riddle-like interview with Arrabal on the Viva La Muerte DVD, and I really couldn't tell.) Enacted in some kind of post-apocalyptic wasteland akin to the one in El Topo--with jagged rocks and forbidding, shadowy hills replacing El Topo's vast desert--it's an avant-garde film in the Panic mold, a film to enrage rather than to be enjoyed. Since most of the modern-day, film-savvy viewers will not be enraged, it acts more as a curiosity piece, a stunt in the mold of John Waters which has an ending more haunting and moving than it really ought to be--a testament to Jodorowsky's budding skill as a filmmaker. The "story" follows childish lovers Fando--Arrabal's surrogate--and Lis, who is paralyzed and pulled by Fando in a wagon as they journey toward the mythical city of Tar, a paradise which probably doesn't exist. Along the way they meet various corrupt temptations, Pilgrim's Progress-style, including a pack of transvestites and some lecherous old men. It should have been a short film, but it does attain a certain power by its conclusion, however inevitable and predictible the actual results are. Supposedly the film caused a riot at the Acapulco Film Festival where it premiered in 1968, and Jodorowsky barely escaped from the screening alive. Well, it was that kind of year.

The storytelling is much more distinct in El Topo than in his preceding film, Fando y Lis, but that may have much to do with the fact that he's adapting another's material. Fando y Lis is a play by Arrabal, and Jodorowsky directed it, he says, without a script and from memory, though one can imagine that the result is something with which Arrabal was pleased. (I watched the riddle-like interview with Arrabal on the Viva La Muerte DVD, and I really couldn't tell.) Enacted in some kind of post-apocalyptic wasteland akin to the one in El Topo--with jagged rocks and forbidding, shadowy hills replacing El Topo's vast desert--it's an avant-garde film in the Panic mold, a film to enrage rather than to be enjoyed. Since most of the modern-day, film-savvy viewers will not be enraged, it acts more as a curiosity piece, a stunt in the mold of John Waters which has an ending more haunting and moving than it really ought to be--a testament to Jodorowsky's budding skill as a filmmaker. The "story" follows childish lovers Fando--Arrabal's surrogate--and Lis, who is paralyzed and pulled by Fando in a wagon as they journey toward the mythical city of Tar, a paradise which probably doesn't exist. Along the way they meet various corrupt temptations, Pilgrim's Progress-style, including a pack of transvestites and some lecherous old men. It should have been a short film, but it does attain a certain power by its conclusion, however inevitable and predictible the actual results are. Supposedly the film caused a riot at the Acapulco Film Festival where it premiered in 1968, and Jodorowsky barely escaped from the screening alive. Well, it was that kind of year. El Topo expands upon the themes of Fando y Lis but Jodorowsky also refines his skill and heightens the art. His third film, The Holy Mountain, was considered a flop upon its release, but only because nobody really had a chance to see it. With the new DVD box set The Films of Alejandro Jodorowsky finally bringing his filmography to a wider audience, it seems that Holy Mountain's reputation is being restored to the point where many critics are now discussing it as the superior film. To be sure, it's the wildest, and the most pure expression of his imagination on film (and thus, even closer to his comics). While it once again blurs genres, it is ostensibly a science fiction piece, set in a world (perhaps the near future) of mass poverty and prostitution and ruled by a corrupt and hypocritical papacy. The symbols and coded imagery come fast and furious from the onset of the film. Here, for example, is the opening: during the credits, we see a black-clad Master (Jodorowsky again), wearing a wide-brimmed hat and a cloak, who is kneeling between two blonde female disciples in some kind of sacred chamber. He strips the women, removes their false fingernails, shaves their heads and pushes them together so that all three form the shape of a mountain: essentially they are foreshadowing the procession of events in the story, as we will see our characters rid themselves of material possessions, achieve a spiritual nakedness, and ascend the mountain to find their transcendence. But then the images come more quickly: models of the cosmos and unblinking eyes, one door opening with another revealing a key, mummified bodies, God knows what else. We see a thief lying in his own urine in the dirt, his face covered in flies. A tarot card lying nearby identifies him as the Fool. A cougar beside him roars. We see another tarot card strapped to the back of a legless and armless man who energetically hobbles through the street toward the Fool, and so on, almost unrelentingly for two full hours! But the narrative is pretty straightforward: this Fool, identified in the film as the Thief, climbs a Tower (like the tower of the Tarot), and within it encounters Jodorowsky's Zen master, who teaches him that he needn't seek gold, because we all have gold within us (he demonstrates this by alchemically converting the man's sweat, urine, and feces into an unattractive lump of gold). Then he--and the tattooed woman who accompanies him--lead the Thief into a chamber with the effigies of various men and women from different planets. Each tells of his world, and it's here, just as the narrative is getting bogged down, that the film takes off, with brilliant bits of satire, astonishing set design, and gleefully Bunuellian blasphemy. Finally, when our cast is introduced, all of the "thieves"--nine for the nine planets--join a mission to climb a holy mountain, at the zenith of which they will find some kind of ultimate meaning or transcendent insight. But even this becomes not quite what we expect, as Jodorowsky breaks the fourth wall, directly addresses the viewer, and demonstrates that all earthly pursuits are "maya," illusion. The imagery in Holy Mountain can be the stuff of nightmares, but only in one scene is it actually intended to be--when each of the pilgrims face their darkest fear. For the rest of the film, the extreme images are strangely defused by Jodorowsky's matter-of-fact handling of the material. Corpses mechanized to provide sex shows, a giant phallic ice sculpture assaulted at a banquet by lustful upperclass women, a room full of severed testicles preserved in jars--Jodorowsky observes these peculiar sights like a bemused documentarian. In this way, not much seems "shocking." Blood, bodies, sex, and mud are all part of the same continuum. His excitement for his own ideas translates to the screen, and his best scenes pick up on this electric energy with a pulsating rhythm to the editing: the aforementioned scene of the legless man hobbling quickly through the street; a reenactment of Spain's conquering of Mexico with frogs meticulously disguised as Aztecs and iguanas playing conquistadors; a montage of religious-themed weaponry set to a guitar-rock soundtrack; the demonstration of an immense robot vagina which must be stimulated by penetrating it with a giant, awkwardly-wielded rod--which ends with a perfectly edited gag.

El Topo expands upon the themes of Fando y Lis but Jodorowsky also refines his skill and heightens the art. His third film, The Holy Mountain, was considered a flop upon its release, but only because nobody really had a chance to see it. With the new DVD box set The Films of Alejandro Jodorowsky finally bringing his filmography to a wider audience, it seems that Holy Mountain's reputation is being restored to the point where many critics are now discussing it as the superior film. To be sure, it's the wildest, and the most pure expression of his imagination on film (and thus, even closer to his comics). While it once again blurs genres, it is ostensibly a science fiction piece, set in a world (perhaps the near future) of mass poverty and prostitution and ruled by a corrupt and hypocritical papacy. The symbols and coded imagery come fast and furious from the onset of the film. Here, for example, is the opening: during the credits, we see a black-clad Master (Jodorowsky again), wearing a wide-brimmed hat and a cloak, who is kneeling between two blonde female disciples in some kind of sacred chamber. He strips the women, removes their false fingernails, shaves their heads and pushes them together so that all three form the shape of a mountain: essentially they are foreshadowing the procession of events in the story, as we will see our characters rid themselves of material possessions, achieve a spiritual nakedness, and ascend the mountain to find their transcendence. But then the images come more quickly: models of the cosmos and unblinking eyes, one door opening with another revealing a key, mummified bodies, God knows what else. We see a thief lying in his own urine in the dirt, his face covered in flies. A tarot card lying nearby identifies him as the Fool. A cougar beside him roars. We see another tarot card strapped to the back of a legless and armless man who energetically hobbles through the street toward the Fool, and so on, almost unrelentingly for two full hours! But the narrative is pretty straightforward: this Fool, identified in the film as the Thief, climbs a Tower (like the tower of the Tarot), and within it encounters Jodorowsky's Zen master, who teaches him that he needn't seek gold, because we all have gold within us (he demonstrates this by alchemically converting the man's sweat, urine, and feces into an unattractive lump of gold). Then he--and the tattooed woman who accompanies him--lead the Thief into a chamber with the effigies of various men and women from different planets. Each tells of his world, and it's here, just as the narrative is getting bogged down, that the film takes off, with brilliant bits of satire, astonishing set design, and gleefully Bunuellian blasphemy. Finally, when our cast is introduced, all of the "thieves"--nine for the nine planets--join a mission to climb a holy mountain, at the zenith of which they will find some kind of ultimate meaning or transcendent insight. But even this becomes not quite what we expect, as Jodorowsky breaks the fourth wall, directly addresses the viewer, and demonstrates that all earthly pursuits are "maya," illusion. The imagery in Holy Mountain can be the stuff of nightmares, but only in one scene is it actually intended to be--when each of the pilgrims face their darkest fear. For the rest of the film, the extreme images are strangely defused by Jodorowsky's matter-of-fact handling of the material. Corpses mechanized to provide sex shows, a giant phallic ice sculpture assaulted at a banquet by lustful upperclass women, a room full of severed testicles preserved in jars--Jodorowsky observes these peculiar sights like a bemused documentarian. In this way, not much seems "shocking." Blood, bodies, sex, and mud are all part of the same continuum. His excitement for his own ideas translates to the screen, and his best scenes pick up on this electric energy with a pulsating rhythm to the editing: the aforementioned scene of the legless man hobbling quickly through the street; a reenactment of Spain's conquering of Mexico with frogs meticulously disguised as Aztecs and iguanas playing conquistadors; a montage of religious-themed weaponry set to a guitar-rock soundtrack; the demonstration of an immense robot vagina which must be stimulated by penetrating it with a giant, awkwardly-wielded rod--which ends with a perfectly edited gag. Another moment is in Santa Sangre (1989), Jodorowsky's return to filmmaking after a long absence: a sudden cut to a bird sailing over a city while throbbing salsa music plays; or, even better, a group with Down's syndrome being led by a drug dealer in a dance down a street of prostitutes--the closest, perhaps, that Jodorowsky has ever come to filming a musical. When I saw him introducing a double-feature of Holy Mountain and Santa Sangre in Toronto a few years ago, he seemed embarrassed by the exhausting symbology of the former, and introduced Santa Sangre as his personal favorite. Truly, it represents an evolution in his storytelling, which you can chart more gradually by reading his French comics and (I assume) novels and essays. If El Topo riffed on the Western genre, and Holy Mountain on science fiction, Santa Sangre is Jodorowsky's take on horror; it's produced by Claudio Argento, who likely insisted upon a lot of gore and creative murders, but it reveals itself slowly as an extension of the director's psychology-driven philosophies. Fenix (Axel Jodorowsky, one of the director's sons), imprisoned in a mental institution, recalls his past: the little mute girl he loved; his father, who scarred his chest in the shape of an eagle as a rite of passage; the traumatic moment when he witnessed his mother's arms being cut from her body by her sadistic, philandering husband. He now serves his mother, worships her, even acts as her arms so that she can play the piano again and preen before a mirror; but he has lost his own identity in the process, and is driven to murder by her jealous whims. It's a little bit like Hitchcock's Psycho (as Jodorowsky proudly admits), but the whole mix is something you've never seen before, as original as the elephant funeral scene which occurs early in the film, and about which Roger Ebert has written so eloquently. (Ebert is one of the film's most vocal admirers.) If Holy Mountain was, as Jodorowsky explains on his commentary track, a film made to change the world, Santa Sangre is a film made to change the individual--a plea to free oneself from the grip of one's parents and to forge a new identity.

Another moment is in Santa Sangre (1989), Jodorowsky's return to filmmaking after a long absence: a sudden cut to a bird sailing over a city while throbbing salsa music plays; or, even better, a group with Down's syndrome being led by a drug dealer in a dance down a street of prostitutes--the closest, perhaps, that Jodorowsky has ever come to filming a musical. When I saw him introducing a double-feature of Holy Mountain and Santa Sangre in Toronto a few years ago, he seemed embarrassed by the exhausting symbology of the former, and introduced Santa Sangre as his personal favorite. Truly, it represents an evolution in his storytelling, which you can chart more gradually by reading his French comics and (I assume) novels and essays. If El Topo riffed on the Western genre, and Holy Mountain on science fiction, Santa Sangre is Jodorowsky's take on horror; it's produced by Claudio Argento, who likely insisted upon a lot of gore and creative murders, but it reveals itself slowly as an extension of the director's psychology-driven philosophies. Fenix (Axel Jodorowsky, one of the director's sons), imprisoned in a mental institution, recalls his past: the little mute girl he loved; his father, who scarred his chest in the shape of an eagle as a rite of passage; the traumatic moment when he witnessed his mother's arms being cut from her body by her sadistic, philandering husband. He now serves his mother, worships her, even acts as her arms so that she can play the piano again and preen before a mirror; but he has lost his own identity in the process, and is driven to murder by her jealous whims. It's a little bit like Hitchcock's Psycho (as Jodorowsky proudly admits), but the whole mix is something you've never seen before, as original as the elephant funeral scene which occurs early in the film, and about which Roger Ebert has written so eloquently. (Ebert is one of the film's most vocal admirers.) If Holy Mountain was, as Jodorowsky explains on his commentary track, a film made to change the world, Santa Sangre is a film made to change the individual--a plea to free oneself from the grip of one's parents and to forge a new identity. He made two other films--Tusk (1980), a film that's almost impossible to see now, and The Rainbow Thief (1990), which Jodorowsky filmed as a favor for a friend--but he has disowned both. I'll withhold judgment until I've seen them. But I maintain that the best work Jodorowsky has done is not on film but in the medium of comics. After an aborted attempt in the late 70's to film an adaptation of Frank Herbert's Dune, Jodorowsky decided instead to create a science fiction comic book with one of that film's art designers, Jean Giraud, aka Moebius (creator of the Western comic book Blueberry). Moebius is generally considered one of the greatest living illustrators in comics, and The Incal is regarded--particularly in Europe, where it is better known--as a masterpiece of the form. Once again influenced by the Tarot (Jodorowsky has the largest Tarot collection in the world, and is considered an authority on the subject), the four-part epic is built around four consecutive movements--up, down, left, and right--as its bizarre, semi-comical cast, led by John DiFool (an everyman standing in for the "Fool" of the Tarot), explore a vertical metropolis built into a chasm in a planet and ruled by a tyrannical hermaphrodite and his/her "technopriests"--and then journey to the edges of the cosmos. Unlike most of Jodorowsky's comic book work, this has been intermittently made available in English, first in four lavish volumes published by the Marvel imprint Epic, and more recently from the (sadly, now-defunct) Humanoids Publishing.

He made two other films--Tusk (1980), a film that's almost impossible to see now, and The Rainbow Thief (1990), which Jodorowsky filmed as a favor for a friend--but he has disowned both. I'll withhold judgment until I've seen them. But I maintain that the best work Jodorowsky has done is not on film but in the medium of comics. After an aborted attempt in the late 70's to film an adaptation of Frank Herbert's Dune, Jodorowsky decided instead to create a science fiction comic book with one of that film's art designers, Jean Giraud, aka Moebius (creator of the Western comic book Blueberry). Moebius is generally considered one of the greatest living illustrators in comics, and The Incal is regarded--particularly in Europe, where it is better known--as a masterpiece of the form. Once again influenced by the Tarot (Jodorowsky has the largest Tarot collection in the world, and is considered an authority on the subject), the four-part epic is built around four consecutive movements--up, down, left, and right--as its bizarre, semi-comical cast, led by John DiFool (an everyman standing in for the "Fool" of the Tarot), explore a vertical metropolis built into a chasm in a planet and ruled by a tyrannical hermaphrodite and his/her "technopriests"--and then journey to the edges of the cosmos. Unlike most of Jodorowsky's comic book work, this has been intermittently made available in English, first in four lavish volumes published by the Marvel imprint Epic, and more recently from the (sadly, now-defunct) Humanoids Publishing. Humanoids, for a time, vitally reprinted many significant Jodorowsky tales: Son of the Gun, an El Topo-like gangster saga in which a killer, born with a tail but also a talent for sharpshooting, finds himself on an unexpected journey to sainthood after his life of crime self-destructs in a most Oedipal fashion, The White Lama, an excellent Tibetan adventure into Buddhist myth with magical transformation and even a yeti, and--set in the world of L'Incal--The Technopriests and The Metabarons. The latter is particularly noteworthy, the story of a clan of intergalactic male uber-warriors: to bear the title of "Metabaron," the son must lose a limb or appendage at an early age, replacing it with something cryogenic, then train himself in combat until he reaches young adulthood, when he must defeat his father in battle. Each son must follow this pattern for the simple reason that it's the life that his father led, and each successive generation attempts to break the chain, but is drawn inexorably back toward it. In this way, The Metabarons echoes Santa Sangre, and Jodorowsky's own ideas that the most important battle is to escape the shadow of one's family.

While most of his comics are serials that stretch over multiple volumes, they all have a beginning, middle, and end, and are not the self-perpetuating arcs of most comics. Every story he tells has a point. But some of his strongest tales are in a shorter format, such as those which have periodically appeared in the anthology Metal Hurlant. In one story, "Tears of Gold," a child is given the titular tears, and his family becomes so dependent upon the income granted by his tears that they struggle to keep him in a perpetual state of misery and grief. It's a brilliant satire in the form of a fable. Though he's worked with many artists over the decades, Jodorowsky collaborated with Moebius time and time again, most notably on Madwoman of the Sacred Heart (out of print here, but available for a while from Dark Horse Comics), an erotic satire in which a stuffy professor (a stand-in for Jodorowsky himself) abandons his inhibitions and follows his lust for a young student, only to find himself, ultimately, caught in the middle of a guerilla war! A far cry from the chauvenism of El Topo, Madwoman finds Jodorowsky willing to poke fun at the idea of machismo and casually subverts the expectations of the erotica narrative.

While most of his comics are serials that stretch over multiple volumes, they all have a beginning, middle, and end, and are not the self-perpetuating arcs of most comics. Every story he tells has a point. But some of his strongest tales are in a shorter format, such as those which have periodically appeared in the anthology Metal Hurlant. In one story, "Tears of Gold," a child is given the titular tears, and his family becomes so dependent upon the income granted by his tears that they struggle to keep him in a perpetual state of misery and grief. It's a brilliant satire in the form of a fable. Though he's worked with many artists over the decades, Jodorowsky collaborated with Moebius time and time again, most notably on Madwoman of the Sacred Heart (out of print here, but available for a while from Dark Horse Comics), an erotic satire in which a stuffy professor (a stand-in for Jodorowsky himself) abandons his inhibitions and follows his lust for a young student, only to find himself, ultimately, caught in the middle of a guerilla war! A far cry from the chauvenism of El Topo, Madwoman finds Jodorowsky willing to poke fun at the idea of machismo and casually subverts the expectations of the erotica narrative.Perhaps this was in answer to producer Allen Klein's ill-conceived demand that Jodorowsky film an adaptation of the S&M erotica classic The Story of O, which led to much animosity and a decades-long fight which kept El Topo and The Holy Mountain unavailable in North America (which, in turn, only increased the reputation and notoriety of the films, and thus demand). This fight always seemed out of character for Jodorowsky, who, as he aged, seemed to actually become the saintly Zen master that he pretended to be in his films. He conducted classes in "psycho-magic" and urged his attendants to free themselves of the demons of their past, but at the same time would always reserve most hateful words for Klein (and Klein for Jodorowsky). Thus it was with great relief that those of us in attendance for the Toronto double-feature screening heard him proclaim that he had finally met with Klein again, and all the animosity dissipated the instant they saw each other, after so many years, face to face. They marvelled at their white hair, laughed, and embraced, and the result--this May of 2007--is a long-awaited Region 1 DVD box set entitled The Films of Alejandro Jodorowsky. It will do much to restore his reputation in the States, with its splendid transfers of El Topo (presented in Spanish, at last) and The Holy Mountain. (The presentation of Fando y Lis is reportedly inferior to the earlier, out-of-print Fantoma disc, but I haven't made the comparison yet.) The box also comes packaged with some invaluable rarities: his short film "La Cravate," which had been thought lost, and now sheds light on his mime work; deleted scenes for Holy Mountain and audio commentary for all three films; and CD soundtracks for El Topo and The Holy Mountain, the latter being released for the first time. Santa Sangre, his finest film, remains only available in Region 2, but that one's a lavish special edition which new fans will find to be worth seeking out.

El Topo and The Holy Mountain continue to astonish. When El Topo played at the Wisconsin Film Festival last month, audiences were shocked and delighted--at once--by the film's audacious ideas and stunning visuals. When it was over, they immediately began to debate whether they had just seen a triumphant work of art or a pretentious mess. His films can still produce a scandal decades later! What I treasure the most about Jodorowsky--and the reason I made a pilgrimage to Toronto to meet him a few years ago--is not his teachings, which pragmatically sort through psychoanalysis and Buddhism to form a kind of secular spirituality, but for his prodigious imagination. For me, Jodorowsky offers not necessarily a penetrating insight into the soul, but a key as to how to let loose the imagination while keeping it guided upon the rails of the intellectual. His stories, in film or in comics, are completely unpredictable, and the only formula or dogma upon which they rely is that everything must change. In a Jodorowsky story, there is no absolute "good" or "evil" character, and if one seems to be one or the other, he or she will undoubtedly switch positions by the story's end. (In this regard, his stories have something in common with those of the anime director Hayao Miyazaki.) So for all of his extreme subject matter and imagery, ultimately his stories are philosophical and optimistic. They are stories of rehabilitation and transformation, in which characters must first look within themselves to root out the corruption or to seek out the pure ideal, and then be born anew. They are stories in which the spirit battles the flesh, and then, unexpectedly, neither conquers, but both are reconciled. They are stories in which every death mirrors or accompanies a birth, for even childbirth is a violent act, and life, at any rate, is a continuum. They are not just stories, but bright sparkling citadels against a desolate horizon of genre and mediocrity. His works are an inspiration--naturally, for they are machines whose designed function is to inspire.

.jpg)